In the summer of 1914 most of Europe plunged into a war so catastrophic that it unhinged the continent’s politics and beliefs in a way that took generations to recover from. The disaster terrified its survivors, shocked that a civilization that had blandly assumed itself to be a model for the rest of the world had collapsed into chaotic savagery beyond any comparison. In 1939 Europeans would initiate a second conflict that managed to be even worse – a war in which the killing of civilians was central and which culminated in the Holocaust.

To Hell and Back (2015) is an apt title for a book on Europe’s horrendous history from 1914 to 1949, a time of global instability that I call the Crisis of the 20th Century. There are few historians better qualified to write this book than Ian Kershaw, for many years one of the world’s leading English-language experts on Nazi Germany. He does not disappoint.

This is a masterclass of big-scale history. When he’s not covering his specialist subject, Kershaw is drawing from loads of works of other historians, having taken the time to read about every single country. You will not find a game-changing theory here like his concept of Working towards the Führer, but he excels at joining the dots and showing how one event led to another. I also appreciated a chapter on “Quiet Transitions in the Dark Decades” and a surprising decision to continue for four years beyond the Second World War, covering its aftermath and the beginnings of the Cold War. Given that he had covered the aftermath of the First, this made sense.

Despite its sweeping breadth and straightforward writing, it never gets dry. It is seasoned from time to time by accounts of the people on the ground. One is the memoirs of a Polish mayor that sheds light on the destruction that unfolded on the Eastern Front of the First World War, an aspect little known here in Britain. As awful as the trenches of the Western Front were, they at least kept most of the fighting away from civilians.

Asking why

When we studied history at school, we tended to take it as a given that the communists came to power in Russia, the fascists came to power in Italy and so on. But we weren’t encouraged to ask: why? Why did those things happen, instead of, say, the other way round? Did the First World War lead to the Second, and if so, why did it not lead to a Third two decades later? One of the best things about the book is that Kershaw sometimes takes the time to explore these questions, even if there are no easy answers.

The impression you get was that the events that unfolded weren’t always inevitable, but leaders were prisoners of their times more often than its makers. Kershaw emphasises that putting Adolf Hitler in the chancellorship was the choice of Germany’s conservative elites, after an election where the Nazis’ support had slipped. But you also get the impression that their fears of the left (especially communists) and need for public support gave them clear and strong incentives to ally with the Nazis.

Likewise, the outbreak of the First World War owed a lot to chance and contingency. There had been similar crises in the previous few years, in Morocco and the Balkans. But Europe had become a powder keg, and preventing war in 1914 may not have prevented it forever. The years before the war may be known in hindsight as the Belle Époque (“Beautiful Era”), but Kershaw makes an important observation that the roots of the European crisis can be traced to this era, even unpleasant ideas like scientific racism and eugenics. Anti-Semitism was often stirred up by conservative elites as way to distract from their own unpopularity, and much violence was “exported” to colonies elsewhere.

Kershaw identifies four underlying factors that destabilised the continent:

- An explosion of ethnic-racist nationalism;

- Bitter and irreconcilable demands for territorial revisionism;

- Acute class conflict – now given concrete focus through the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia; and

- A protracted crisis of capitalism (which many observers thought was terminal).

Influenced by John Keane and Roman Krznaric, I would add a fifth: the rise of mass media. Although newspapers were already widespread, the early 20th century saw new types of media emerge, first the downmarket Yellow Press and later the radio and cinema. These allowed leaders to build a stronger connection with their followers – a boon for both communist and fascist dictators.

These factors did not cause the First World War but fed into it and fuelled further fires for the next three decades, culminating in the Second World War. A subchapter on the latter covering the Holocaust and other atrocities is titled “The Bottomless Pit of Inhumanity” and that really says it all. By 1945, Europe might’ve looked like a collection of failed states with no future and no hope.

And yet, history is a surprising beast, full of not just the good that leads to bad, but also the bad that leads to good. Against all odds, the Crisis came to an end, and next four decades were a cocoon of peace and prosperity. Kershaw argues that the factors behind this were:

- The total defeat of Germany.

- The (relatively modest) purges of the surviving Nazis and their collaborators.

- The stable division of Europe between the US-aligned West and Soviet-dominated East.

- Adding to the above, the fear of nuclear war.

- The brutal expulsions of ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe and other population displacements, which reduced the number of ethnic divisions.

Other changes are hinted at. John Maynard Keynes made some important discoveries in economics before the Second World War, but it was only after that his ideas became influential.

East and West

Warsaw at the end of the Second World War, 85% of its buildings destroyed.

For those who believed that modernity meant inevitable progress to a happier, richer and tamer world, the Crisis of the 20th Century was a rude awakening. But those who feared the modern world weren’t exactly right either. The worst violence was not in the richer, more modernised Northwest of Europe, but in its poorer, less modernised East. For those decades, Eastern Europe was probably the single most dangerous place to live on Earth. Poland lost about 17% of its population in the Second World War, about six times more than the Netherlands and seventeen times more than Britain. It had already been devastated during the First, then invaded by the Soviets. It makes you wonder if the four decades of communist rule felt like a relief.

The further east (and south) you went in Europe, the less modernised it was – less literacy, urbanisation, democracy and material wealth. But unlike the poorer parts of the world, many with their own troubled and violent histories, Europe’s East had specific factors that made it volatile. It was poorer than the Northwestern countries but couldn’t just be carved up among them like Africa; its people were more exposed to ideas like representative democracy, nationalism and socialism.

The East-West pattern is also important to understanding the roles of Europe’s two most populous countries. Russia, mighty in population and area, was its poorest. It had a long history of violent, despotic rule since the time of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century, if not earlier. This created a rare situation where the old order was so hated that communists could overthrow it, yet also a foundation for the madness of Stalin’s purges. Elsewhere, the elites could forge political coalitions against communism, whether democratic or not.

Meanwhile, Germany, the continent’s “pivotal centre” and second-largest population, lay on the threshold of both the industrialised Northwest and the volatile East. As Kershaw notes, in the early 1920s:

…Germany was more enigmatic. It fitted neatly into neither the model of relatively well-established democracies of the more economically advanced north-western Europe, nor the model of the newly created, fragile democracies of eastern Europe. In many ways, Germany was a hybrid. It looked both west and east. It had both an extensive industrial proletariat, like Britain and France, but also a large peasantry, especially in its eastern regions, whose values were rooted in the land.

He goes on to compare other contrasting aspects of Germany, like how the Weimar Republic both built on a substantial democratic tradition and yet felt like a flimsy foreign import.

Though Germany was a rich country, it had contrasts with the British Isles, Low Countries and Scandinavia, where parliaments and elections were embedded in their political systems’ DNA. In the aftermath of the First World War, Ireland and Finland both struggled for independence and underwent brutal civil wars, yet both emerged from the struggles with democratic political systems that gained wide support and have endured to this day.

Many of these richer countries had an additional defence: they defined their nation through citizenship and longstanding institutions, rather than as a group of ethnic people. This aspect was missing in Germany. The political system created by Otto von Bismarck was swept away after 48 years. It was therefore much easier for the Nazis to sweep away its successor after 14. In just six months after Hitler’s rise to power, almost every national institution had been either Nazified or crushed.

It also made a crucial difference that the Northwestern states were more homogeneous, compared to interwar Poland where Poles were only two-thirds of the population. This created divides between minorities, who often wanted to form their own country or join with a neighbour, and majorities, who resented them in the best of times. Partition was not always an easy answer, as these groups often lived in the same cities.

The Treaty of Versailles is widely maligned in hindsight. There were mistakes. The demand for German reparations was disastrous, not economically but politically. But the impression I get is that its framers faced impossible choices, caught between the new politics of democracy and the old politics of imperialism, both of which had very real power.

It was all very well to speak of the lofty ideals of democracy and “self-determination”, that all peoples should be able to decide their political futures. But how would that work in regions like the western Balkans which were divided between many ethnic groups, often living in the same cities and some speaking virtually the same language? Uniting them could create a more powerful state and avoid a difficult partition, but would it be worth the risks?

In the 1920s, nearly all the newly-created democracies in the East proved ungovernable, thanks to ethnic and class divisions. Some, like Hungary, never got off the ground. After a revolving door of governments, Poland’s was overthrown by an army general in 1926. Most others collapsed by the mid-1930s, apart from Czechoslovakia, which hung on until the Nazi invasion.

There were less ethnic divisions in the Northwest. But moreover, when they existed, such as between the English and Scots or the Flemish and Walloons in Belgium, they did not destabilise the countries. Ethnic divisions weren’t necessarily a problem on their own, because each one was a different case.

The triumph and failure of communism

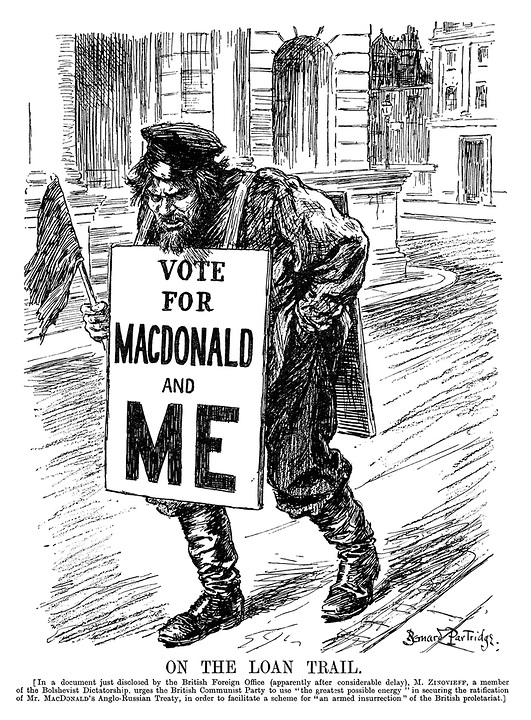

A political cartoon ahead of the 1924 British general election, showing a caricature of a Bolshevik and linking him to the socialist prime minister Ramsay MacDonald.

Class conflict, like Europe’s other ills, had roots in the Belle Époque. Before the First World War, European elites had feared the growing support for socialism. By the 1920s, socialist parties had replaced liberal ones as the dominant force of Europe’s political left.

But the rise of a communist regime in Russia was a game-changer. For many left-wing activists and intellectuals, the appearance of “A New Civilization” was exciting. They had long assumed it as a fact that capitalism was on its last legs, and the Great Depression seemed to confirm it. The excitement was maintained throughout the 1930s, even as news of the brutal purges began to break.

When studying Soviet history at school, we were fully aware of this dark side to Joseph Stalin’s rule. Yet I still got the impression that for all the regime’s brutality and lies, there was something impressive about the industrialisation that happened under it. They certainly knew how to create powerful visual images of the apparent progress. Was it really doing something impressive?

In some ways, yes. The regime could squeeze money for investment out of its citizens in a way that no other country would’ve tolerated, many of which went into impressive projects like electrification, the Moscow Metro and whole new cities like Magnitogorsk. The price was much suffering for its own people and the most repressive regime in the whole of Europe. Overall growth was steady rather than explosive, apart from in the late 1930s when the purges dented it. Its economic isolation, normally bad for an economy, worked in its favour at a time when the rest of the world was hit by the Great Depression. In fact, the material impact of Stalin’s policies appears to have been mixed.

Outside of the Soviet Union, the left were on the backfoot, and the spectre of communism played an important role. In most countries, it split the left between socialists who wanted to win power at the ballot box and communists who were in league with Moscow. Moreover, fears of communism were a powerful rallying force for the right, whether moderate or extreme. Both of these factors were disastrous for the left, most fatefully in Germany.

There is an age-old question among the left: does a ‘radical flank’ help or hinder your cause? I think the answer has varied by time and place, but during the Crisis the answer was no.

The allure of fascism

Rally of the Italian Fascists in 1931. They were the main inspiration for the Nazis, who would soon overshadow them.

What is fascism? In 1944, George Orwell complained that the word had been used for so many things that it had become “almost entirely meaningless”. Fascists, too, couldn’t agree on it. In 1934, an attempt to organise an international organisation for fascism failed, partly because Nazi Germany didn’t turn up.

For Kershaw, what sets fascist regimes apart from other right-wing regimes is that they are unconservative. While there were many right-wing dictators in 1930s Europe, they were mostly trying to “conserve the existing social order”. Fascism is different. It wants to sweep that order away. It is not about freezing or turning back the clock but creating something new, based on some “special” quality of the nation. Other common elements include:

- Obsession with national unity, including “the cleansing of those deemed undesirable – foreigners, ethnic minorities, ‘undesirables’”.

- Racial exclusiveness, though not necessarily biological racism like in Nazism.

- Extreme and violent opposition to political enemies, especially communists.

- Stress on discipline, manliness and militarism – almost all of them had a uniform.

- Sometimes, expansionist or irridentist goals. Some, in the smaller and more democratic countries, had no interest in this at all, a big contrast with the radicalisation of Nazi Germany.

- Sometimes, anti-capitalism as well. Benito Mussolini’s concept of corporatism was midway between free markets and socialism.

Kershaw deems Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany to be the only countries where true, homegrown fascists came to power. Like Hannah Arendt, he draws comparisons between the fascists and the Soviet Union, though rather than emphasise the “totalitarian” concept, he argues that their chief similarity was that they were “dynamic dictatorships”, seeking to change society in some way.

He sums up the factors that led to the rise of fascism:

- “The complete discrediting of state authority” – street violence between fascists and communists preceded the rise to power of the former.

- “Weak political elites who could no longer ensure that a system would operate in their interests” – though they disliked the fascists’ vulgar demagoguery, conservative elites played crucial roles. Neither Mussolini nor Hitler seized power. They were invited into power, by conservative heads of state.

- “The fragmentation of party politics” – in both cases, a revolving door of governments further served to discredit a democracy, making the countries look ungovernable without autocracy.

- “The freedom to build a movement that promised an alternative” – fascism came to power in two ailing democracies that failed to stand up to them. Some reactionary regimes, like Portugal and Hungary, actually banned local fascist parties, while Britain and France imposed limits on them.

Although economic woes acted as a tipping point in Germany, it was really faults with the political system that brought the fascists to power.

The rise of fascism was not unstoppable. It appears to have declined in most countries in the late ’30s. In Italy, Kershaw finds evidence that Mussolini’s support was “on the wane”. This invisible trend could not prevent the radicalisation of Nazi Germany, but it may be one reason why these movements never came back after the war.

Learning from history

War damage in Kharkiv in 2022, in the first week of the Russian invasion.

So how does the past century’s crisis compare the emerging crisis we face today?

I write this over three years after war returned to Europe, at a time when democracy is in its greatest crisis since the Second World War and we’re seeing the rise of the far right, nationalism and militarism, and the scapegoating of foreigners and minority groups. Often, the response from others has been to ask “Will people learn from history?” I’m depressed to say, no, that kind of message doesn’t work, and we’re going to need another route.

Like the old crisis, the new one is fuelled by economic woes, social divisions, uncertainty about the future of nations in a changing world and especially public disgust with politicians. And, crucially, no hope. This is a contrast to Russia in 1917 where right-wing demagogues were notably absent (of course, that opened a can of worms of its own). Meanwhile, the centrist old guard is collapsing and the radical left is yet to offer a viable alternative. To paraphrase a letter from Antonio Gramsci, written in one of Mussolini’s jails, “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born.” I don’t need to hammer home how much the current world has parallels to the Crisis of the 20th Century.

And yet, there are differences. It is a mistake to assume that every demagogue is a new Hitler. There are aspects of that period of history that will not be repeated. The details in each time and place are important. But there are broader changes too.

A big change is that European countries have become more like each other, and the challenges they face have become more global. The impression you get is that during the Crisis, governments were either democratic or not – there were few if any hybrid regimes. There were stark contrasts between the fates of different countries. Two contrasting movements seized power in Russia and Germany, while being merely disruptive in France and peripheral in Britain. Most of Europe’s conflict could’ve been avoided if its political cultures had been more like its healthiest ones.

The modern crisis of democracy and the decent society is a global challenge, and Northwestern Europe is threatened too. The United States has gone from being a safe haven to a flashpoint. And besides economic let-downs, there are other global challenges, like AI, the social effects of migration and especially climate change, that have no equivalent back then.

Like the old crisis, the emergence of new, disruptive media has destabilised the political order. The difference is that the disruptive media back then, especially cinema, required extensive manpower, costs and know-how. Any yahoo can post on social media. This is a double-edged sword. It will be harder to maintain a centralised dictatorship – or a stable democracy.

There is good news too. Democracy has tended to bend rather than break. Instead of seeing brazen putsches, it has tended to be eroded gradually. Modern autocrats like Donald Trump and Victor Orbán pay lip service to democratic traditions while undermining them in practice. There is still a chance that an alternative will be possible through whatever will remain of the democratic system. Meanwhile, compared to Germany in the 1930s, we lack the culture of street violence or an equivalent to the legacy of the First World War, while government institutions like the civil service are not the stodgy conservative bastions that were easily Nazified.

Once again, the lurch to the right feeds off a fear of an extreme left. Back then, the spectre was communism. Today, it is immigration and woke politics, supposedly threatening to suppress your right to free speech and destroy the heritage and identity of your country. These fears can resonate even with moderate voters, a cheap way for right-wing politicians and media to win support at a time when their economic visions are a void. But compared to communism, these modern spectres are toothless, especially woke politics, which passed its peak in 2020. The backlash against them resembles the protagonist of the Weird Al song “First World Problems”.

So what can we learn about our present and future from Europe’s troubled past?

- Progress isn’t always linear. The lesson from the Crisis of the 20th Century is not that progress is absent or bad. The decades of peace afterwards, and the contrasting fates of Western and Eastern Europe during the Crisis, showed that with modern education and technology, things really could get better. In the long run, they did. But above all, the message of the book is that we should beware, because things can also go backwards.

- Politics matters. Although the Great Depression and post-Covid squeeze exacerbated them, the causes of the political woes were mainly political. It’s no good expecting a rich economy or inevitable progress to deliver the best political system — when it has problems, we need to fix it. This is tricky because very few voters care about the nuts and bolts of how the government works. But as Sam Freedman notes, they will care about its consequences.

- Keep people connected to the system. Britain and the Scandinavian countries come across as the healthiest political cultures during the Crisis, followed by the rest of the Northwest. My suspicion is that a big factor was the mass membership of political parties, trade unions and institutions of civil society. They gave people a sense of belonging and connection that might otherwise be directed towards a demagogue. Today, these have been eroded. Political parties can no longer inspire us or fulfil that role, so we need to find new ways of either running them or connecting people to each other and politics, like people’s assemblies.

- Keep the elites connected too. This may not sit well with many, but a key factor in the rise of fascist regimes was that the conservative elites lost faith in the democratic system and decided a demagogue was their only hope. By comparison, in Scandinavia, new socialist governments mediated between the elites and a public appetite for a more socialist society. Above all, avoid sclerosis and chaos.

- Pursuing equality requires pursuing democracy. Political movements that promise equality without democratisation, especially communism, either fail or have unintended consequences. So those who champion a more equal society need to offer a vision for how society can be more democratic. Current identity politics and radical left movements are hitting political dead-ends, so they could propose making more decisions through citizens’ juries and assemblies, for example.

- Be open to new economic ideas. The Great Depression was exacerbated because governments stuck rigidly to policies of balanced budgets and, at first, the gold standard. As Keynes realised at the time, they actually needed to borrow money to stimulate the economy. We’ve learned since from Keynes, but would we listen to a modern counterpart? When politicians insisted in the 2010s that “There is no alternative”, it meant they weren’t even looking.

- There’s always hope. Recovery began at the most unlikely moment, just after everything in Europe had hit rock bottom.

We are facing different challenges now – and indeed, the current crisis is challenging precisely because it is different. History can’t give us all the answers, but it is a great teacher. If you only ever read about one era of history, you should read the history of the continent that made the modern world and how it went to hell and back.

Leave a comment