In April 2012, Bill Shorten, a minister in the Australian government, gave an interview that drew unusually wide attention, and has occasionally been circulated since. The topic was about Peter Slipper, the parliamentary speaker who had temporarily left his post in light of allegations of sexual abuse. Shorten was asked whether Slipper should return to the speaker’s chair:

Shorten: “I understand that the Prime Minister’s addressed this in a press conference in Turkey in the last few hours. I haven’t seen what she said. But let me say, I support what it is that she said.”

Reporter: “Hang on, you haven’t seen what she said..?”

Shorten: “…But I support what my Prime Minister said, so…”

Reporter: “Well what’s your view?”

Shorten: “My view is what the Prime Minister’s view is.”

Shorten went on to become the leader of his party, during which they lost two elections.

Imagine if he’d instead said this:

Shorten: “I don’t know the full details about these allegations. I understand that the Prime Minister’s addressed this in a press conference in Turkey in the last few hours. I haven’t seen what she said. But let me say, I trust her to do the right thing.”

The interview is a somewhat glaring case of an important problem in modern democracy. So too was the situation that had led it. Slipper had been a dubious choice for the speaker’s chair, given an earlier scandal around his travel expenses. But the government had backed him as a ploy to increase their narrow majority, since Slipper came from the opposition but would not cast votes while in the speaker’s chair. For the same reason, the government continued to defend Slipper through a drip-feed of scandal until he stepped down five months later.

An ailing system

Too often, politicians have let voters down because they were serving the party interest rather than the public interest. There is much to be said about how that has stopped governments from being democratic, responsive, competent or ethical. But moreover, it just looks bad, because we see politicians arguing and voting for things that they don’t personally support, and claiming to serve the public interest while actually serving the party interest. It looks dishonest — because it is. In fairness to Bill Shorten, at least he was open about his blind loyalty.

I recent did a piece of satire titled “What if politics were a tennis club?” in which the “Tennis Social Democrats” bicker with the “Tennis Feepayers’ Party”. The point was to show how the system we use to run governments is utterly bizarre compared to how we’d run almost any other democratic organisation, such as a tennis club.

Meanwhile, in his book Power to the People, which will be my next book review, Danny Sriskandarajah hits the nail on the head in describing the system that we have:

…a system that is crippled by its dependence on the campaigning, party-standoff mindset in which complex ideas and critical thinking are reduced to three-word slogans and whatever clear dividing lines can be unearthed or, if need be, fabricated. Filtered through the lens of media outlets whose survival depends on their ability to entertain and, often, arouse division, much of today’s political debate is forced into unhelpfully moralistic narratives. Politicians are encouraged to focus on disparaging the policies and motives of their political opponents and on feeding the media’ addiction to contempt and resentment.

Yet apart from a few microstates, all modern democracies have parties. Although they have different ideas and viewpoints, politicians are generally expected to support and vote for their party line in unison. Disagreement within a party is seen as something that ought to be buried behind the scenes. Why do we have this system, given its obvious problems?

Why political parties have been helpful

Part of the reason that political parties are so widespread is that they have been genuinely helpful, by organising groups of politicians with widely contrasting views to support a cohesive agenda.

If politicians only ever acted on their own convictions or the interests of their own voters, it would be hard to get stuff done. How do you fund the building of a road in Cornwall if most politicians don’t represent the area? How do you legislate for a system of universal healthcare when so many politicians would have different ideas on how the system would work? You might get round some of these issues through negotiations, but not the more complex ones.

Indeed, a lack of party discipline has been precisely the reason why the United States Congress has been famous for gridlock. In 1992, the Democrats won the presidency and both chambers of Congress by decisive margins. This should’ve been a clear green light for the Democrats to realise their hopes of healthcare reform, but it failed due to their divisions, united opposition from the Republicans and opposition from healthcare lobbyists. It wasn’t until 2010 that the Democrats overcame those problems and passed Barack Obama’s modest reform. America gets the worst of a party system; a party can easily unite to block popular progressive policies but not to pass them.

Parties normally get politicians working together by appealing to ambition, even greed. Politicians who toe the party line may be rewarded with a promotion or chance to achieve an aim. Under the whip system, a turncoat or a troublemaker may be demoted, sidelined or even kicked out of the party altogether, which in most countries has typically been a political kiss of death.

The whip system has always been flawed, often rewarding blind loyalty and greed while punishing the healthy kinds of scrutiny and dissent, and encouraging politicians to serve their self-interest rather than the public interest. But at least it got things done.

The other benefit of parties is that they give voters a clear choice in elections. Most voters don’t have the passion or patience to study all the candidates in detail, so parties give them a vague idea of what policies their vote will lead to. This has further reinforced the view that politicians should be loyal to their party. If they don’t they will be seen as not just betraying their party, but also the voters who put them in office.

Why parties have been inevitable

How often do you see one of these for an independent?

There are other reasons why political parties exist that are not necessarily helpful, but the system makes them inevitable.

Many people would like to vote for a local independent but don’t, because they never seem to be contenders. Voters rarely hear about independent in the media, receive leaflets from them or see supporters’ signs outside houses. So they have no reason to believe that there’s any point in voting for independents.

One major reason is that independents who don’t belong to a national movement will miss out on donors and media coverage that operate at a national level. The other is that parties typically have some cause that motivates their activists to organise and campaign. Saying “Vote for me, I’m a local, an independent and a nice guy” isn’t nearly as good for motivating activists.

It is no surprise that independents are more common at the lowest levels of government, where politics is more intimate and councillors are more likely to be elected based on local connections rather than donations, media coverage and motivated activists. Although independents have only occasionally won seats in the British parliament, most parish (i.e. village) councils are nonpartisan. Local governments in Canada and California are also nonpartisan, though political parties sometimes have influence in larger cities.

One additional factor in countries that use list-based proportional voting systems is that isolated independents can’t stand on their own. However, you can have parties that are actually slates of independents, such as the Free Voters that contest local elections in Bavaria.

Things fall apart

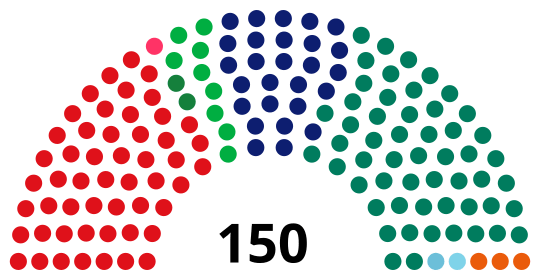

The Dutch parliaments of 1986 and 2023. The former had 9 parties, with the largest having 36% of the seats and another with 35%. The latter had 15 parties, and the largest by far was a far right party with 25%.

Dislike of party culture is nothing new. In 1796, George Washington complained that parties were letting “cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men” to “subvert the power of the people”. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Charles de Gaulle, like Washington, were generals turned politicians who disliked the culture of “partisan quarrels”, as De Gaulle put it.

If we don’t feel represented by parties now, there probably wasn’t truly a time when they did. The historian Richard J. Evans once discovered a trove of files from police spies in 19th century Hamburg, who listened to conversations in beer halls and on the streets. This rare insight into ordinary workers’ conversations showed that their views were more varied than the socialist party that they tended to vote for. In the 1950s, by many counts the healthiest age for British democracy, a study found that only about a third of voters had views resembling the party they voted for.

So why has faith in the system declined? Perhaps the cost-of-living squeeze after Covid, the longer economic letdowns since 2008 and other crises like the climate are part of the problem. But that doesn’t explain how the system survived previous eras of economic squeeze such as the 1970s. Distrust has been gradually gathering pace over the last few decades. It has not relented even during periods of economic recovery such as the late 2010s.

Perhaps the trend to individualisation is affecting voters, similar to the trends that have affected everything from music to funerals. Voters are used to “shopping around” in other areas, as The Economist put it, and voting behaviour is no longer a simple divide of economic class. As a result, most democracies have seen a trend of votes among parties becoming more fragmentated in the last 50 years. Even that may not give them the party they want. This survey of millions of Britons from last year found that only 2% had views that align with a particular party.

The long-term decline of party membership is another factor. It’s certainly harder to feel connected to parties if you don’t belong to one or know someone who does. It has also made parties increasingly dependent on rich donors to stay afloat, further exacerbating the gulf between them and everyone else.

The decline of the traditional power structures has had a knock-on effect. With the rise of 24-hour news media and then social media, it has become easier and often more fruitful to rebel against the party — some examples from the 2010s are Ted Cruz in the US and Boris Johnson in the UK. Another effect of the broad decline in party discipline is that governments have become less effective at passing laws, most obviously the US Congress but Sam Freedman makes the case that it’s affected the UK as well. That gives us even more reason to despise politics.

But also, I suspect that we increasingly dislike the system is that we’re just more exposed to it. In the 1950s, you might have encountered the news once a day in the paper or on the radio. Despite the decline of the print media, the internet lets news organisations reach more people than ever. By 2021, print readership of The Guardian had fallen from its peak by two-thirds, but it was reaching six times as many people online.

…[P]eople get elected as representatives, and then the public sit back, expecting them to do stuff, and get angry when they don’t. For me that method of representative democracy doesn’t really work anymore, if it ever did, because people are more empowered, more knowledgeable, have access to more facts.

The “How” part

So could we really build a nonpartisan democracy? We could do that by making use of democratic innovations, such as citizens’ assemblies and people’s assemblies. By showing that wide agreements on issues is possible, they can reduce the noxious effects of partisanship. We’ll probably still need parliaments and local councils, so change must come to them as well.

When I say that we need to abolish political parties, I don’t mean that they should be banned. Rather, we need to find new ways of organising politics. In fact, that could mean that we still have parties, but more as banners for loose alliances of independents, rather the parties we have today.

Ironically, the only way to bring this would be… a party! But not a traditional one. This anti-party would not use the whip system. Its members would disagree on things, perhaps even some voting against their own budget or leader. Perhaps it would originate on the radical left, but it may not have an ideology at all. And it may fail, but even if it does, it could cajole existing parties into becoming more like an anti-party.

One story I love retelling comes from the English town of Frome, where a group of locals banded together and took over their local council. They agreed to work together while not agreeing on everything, and to make more use of consulting the locals. This helped them avoid the problem that other independent alliances have had, of falling apart after about five years. As a result, they cemented their dominance of the council in the next three elections, to a point where traditional parties didn’t bother to run against them.

But could something like this work at a national level? Could it scale up while maintaining the ethos be a genuine grassroots effort? There is much we don’t know. But if history has taught us anything here, it’s that this is the kind of change that does not come from established institutions, nor from outside forces on the right. If it comes from the radical left, it won’t be from its current mainstays.

The problem with the radical left is their chronic inability to work together. In the last few months, a new radical left party has been launched in the UK, inspiring hope to the hundreds of thousands who signed up that there is an alternative to both the old guard and the far right. On the day I write and post this, the party has been embroiled by infighting that could derail the entire project.

Even if it survives this turmoil, I doubt that democratic renewal will come from a top-down project like Your Party. More likely, it will be a grassroots movement to start people’s assemblies that spreads from town to town and eventually forms federations.

Leave a comment