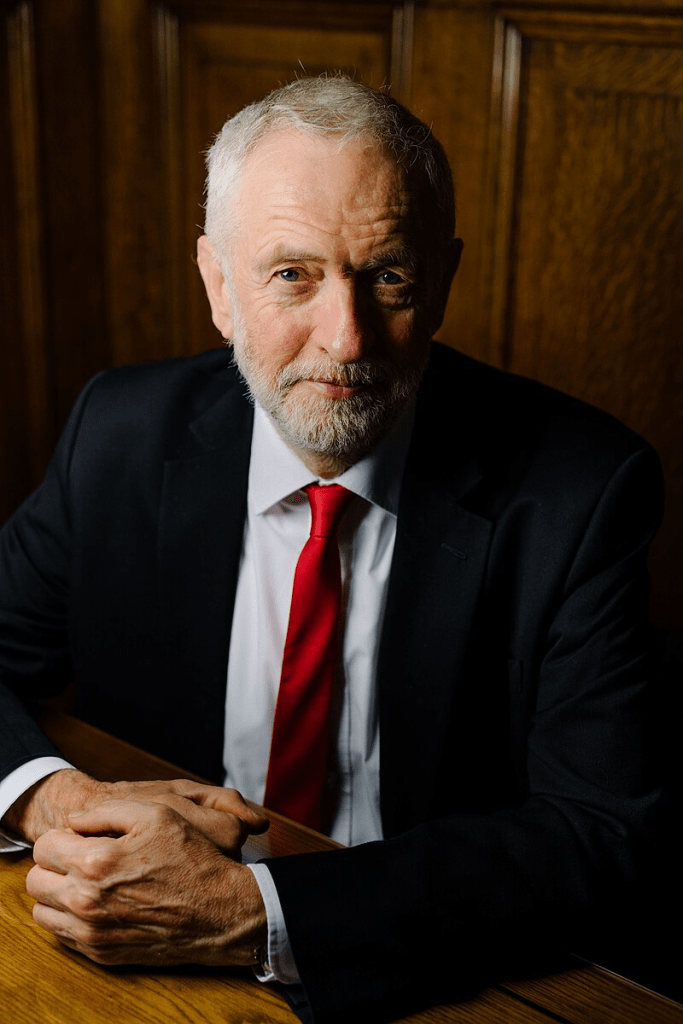

Last month, several left-wing MPs, including a press-ganged Jeremy Corbyn and other exiles from the Labour Party he once led, announced the formation of a new left-wing party. The provisional name Your Party was adopted by fluke, and it may well stick. The party has reportedly received 700,000 sign-ups in less than two weeks. This is a show of enthusiasm that other parties would kill for. It stems from the undeniable frustration with politics-as-usual, economic and social woes, a sense of betrayal by Labour and the rise of the far right at home and abroad.

I have mixed feelings about the new party. It could be the start of a disintegration of the left that paves the way for Britain’s first ever far right government. Or it could be the start of nothing. There are many things that can tear such a movement apart, from the old Trotskyist dinosaurs to the newer identity self-indulgence or even just plain greed for power and status. Or maybe, just maybe, it could be the perfect alternative.

A new party must address a fundamental question: we already have left-wing alternative parties, so what is the point of another? There is a party that runs to the left of Labour that already has 11% of the seats in the current parliament, an effective campaign machine and a charismatic leader — the Liberal Democrats. If you want one that’s more radical than that, there are the Greens. There is indeed something a new party could offer that those two lack, but it’s not a person or a policy.

What do the people want?

I was firmly against Jeremy Corbyn’s rise to the Labour Party leadership back in 2015. For those who don’t know, he was a long-time figure on the party’s hard left who had often held controversial views, some of which had been vindicated by history (e.g. gay rights, opposing the Iraq War) and some not (e.g. sympathies for certain militants). He is in many ways the British counterpart to Bernie Sanders, but more left-wing.

I thought he would lead his party to a disaster not unlike that of 1983. I was right, but also wrong. He led them to a narrower defeat in 2017 and inspired a level of grassroots enthusiasm that many thought was dead, even if it didn’t always translate into campaigning boots on the ground. Many of us couldn’t foresee Corbyn’s appeal to many of the more apathetic voters, often not because of left vs. right games but because he came across as more real and honest than a regular politician.

But they still lost twice, with a rout in 2019 against a Conservative Party that was growing more extreme. I second Neal Lawson’s comments in the Byline Times that the movement needed to reflect on what it should’ve done differently, rather than blaming anyone but themselves.

We cannot just do the same thing again. We should learn from what went wrong, but also from what went right.

Let’s start with the latter. The media and political arena may still think in terms of left vs. right games, but voters increasingly don’t, if they ever did. They are open to many ideas that we’ve been told are too radical to ever be popular. A movement that scratches this itch may not have to be as dependent on the media and business elites as the old guard. Nor does it need to be the slickest game at PR and campaigning. Indeed, the lack of these things may have instead added to Corbyn’s appeal.

Yet still, there was a ceiling to that appeal, even at its high point in 2017. Why was that? The obvious response is to point to well-known problems: the anti-Semitism scandals, Corbyn’s unpopular positions in some areas like foreign policy, the failure to stand up for EU membership and cases of unprofessional and paranoid leadership. But among the people I knew, their problems with the Corbyn movement stemmed less from details than from fundaments.

Part of the problem is the thorny issue of raising taxes. Rather than risk backlash over this, Labour under Corbyn promised spending without a viable plan to fund it, as the Institute of Fiscal Studies pointed out. (They criticised the Conservatives too.) Few voters would’ve heard of this institute, let alone what it said, but many were also sceptical that Labour could massively increase spending without some trade-offs. And if they actually had come to power, this would’ve created a dilemma of whether to raise taxes without a mandate or renege on promises to spend.

Is there another way to fund an ambitious agenda? More taxes on the rich would help, yes, but there’s a limit to what this can raise. Inflationary monetary policy and deficit spending are no recipe for funding a long-time rise in government spending — there is no such thing as a free lunch. If we’re going to have Nordic levels of spending, we’re going to need Nordic levels of taxes.

So a new left-wing party must address the challenge of getting voters to accept higher taxes. History offers a clear lesson here: the more people have a say in politics, the more taxes they will pay. In pre-modern times, a king like Henry VIII or George III could face a rebellion for raising any taxes. Today, tax rates are highest in the Nordic countries because they have the strongest democratic cultures. A new party with a new manifesto is unlikely to change that on its own, and will hit electoral ceilings like Corbyn’s Labour and Podemos in Spain. A new party needs what these have lacked: a vision to democratise the country.

(Corbyn supporters rally in Bristol in August 2016.)

Personalities and tribes

Even for many I knew who supported Corbyn’s Labour, there was another problem, summed up by one word: “cult”. Like Bernie Sanders in the US, Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France and Sahra Wagenknecht in Germany, it was an example of what I call personality socialism, a trend of having a socialist movement which gets overshadowed by the adoration of one man, or less likely one woman. It may have been fun for fans at the Glastonbury Festival to sing “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn” when he came on stage, but for everyone else, things like this can look sinister. Even Corbyn himself disliked it. It also makes the movement vulnerable to media attacks on its leader, especially when those attacks resonate with the public.

There is an interesting question on whether a political movement needs a charismatic leader that people can relate to. In fact, there is a convincing argument that the best leaders mediate rather than dominate, because it’s better to make decisions in groups. Top-down decision-making is often a recipe for disaster, and deep down, it is not what personality socialists’ supporters actually want. And while some people may accrue it better than others, personal charisma comes from standing for something that people like.

Then there was the tribalism. Labour under Corbyn was a scene of unpleasant infighting. His supporters suspected that they were being undermined by factional rivals. They sometimes had a point, but overstated it. Many Labour MPs and party insiders who had been open to working with the Corbyn movement were shut down or even harassed. This is never healthy. Organisations work best when their members can be candid about their misgivings and concerns.

The problem of tribalism appeared in other ways. Corbyn’s supporters also fought each other. And Labour failed to work with the Liberal Democrats and take advantage of their leftward drift. Those two parties narrowly received more votes than the Conservatives in 2019, but as with most British elections in living memory, the Conservatives won against a divided left.

Democratise it

There are already signs that the new party will be vulnerable to infighting. So there are three things it should do, though Roger Hallam may have beaten me to mentioning some of them. Underpinning all of them is that it must have not just aspirations to build a fairer society, but also to democratise it.

Firstly, it should use people’s assemblies at a local level as its local unit for organising. This is partly to keep its supporters in touch with the public. These assemblies should aim to be welcoming, pro-social environments that welcome a wide range of people. If there’s one thing the Conservative Party did well in the heyday of its grassroots membership, it was pro-social organising. A new party can do better.

Secondly, it should use another form of assembly democracy: citizens’ assemblies, or panels selected by sortition. This would be a great way to set policies for a national manifesto and address the problem of taxes. But it could also resolve internal disputes, cutting through the factionalism and careerism which are very likely to plague such a party. I will leave open whether they should be assemblies of its own supporters or the general public. The results may not be so different.

Finally, it should work with other left-wing parties and groups, not just the Liberal Democrats and Greens but also assembly-based movements like Southport Community Independents, Cooperation Hull and Majority. It should emulate the Liberal Democrats in targeting the seats they are best-suited to win, particularly against the right. While one option is to have a formal electoral pact, like the New Popular Front in France, much can also be achieved through informal cooperation, as the existing left did in the general election of last year. This can reduce the problem of vote splitting, though only electoral reform can end it altogether.

If a party can do these things, it would giving itself a positive pro-social environment and a democratic compass. And that would reduce problems like infighting that undermined not just the Corbyn movement, but also the left in general.

While I remain unsure of its prospects, it is at least encouraging is that many key figures in the new party are thinking along those lines. Jeremy Corbyn has been running people’s assemblies in his Islington constituency, as has Jamie Driscoll in Newcastle. Shockat Adam has been in touch with Assemble and its House of the People project. Zarah Sultana has spoken about the importance of community organising. Reports suggest that many of them want to make sure the new party is not just a vote-splitter. Whether that can be more than that remains to be seen.

Leave a reply to Learning from Zohran Mamdani’s victory – Assembly Project Cancel reply