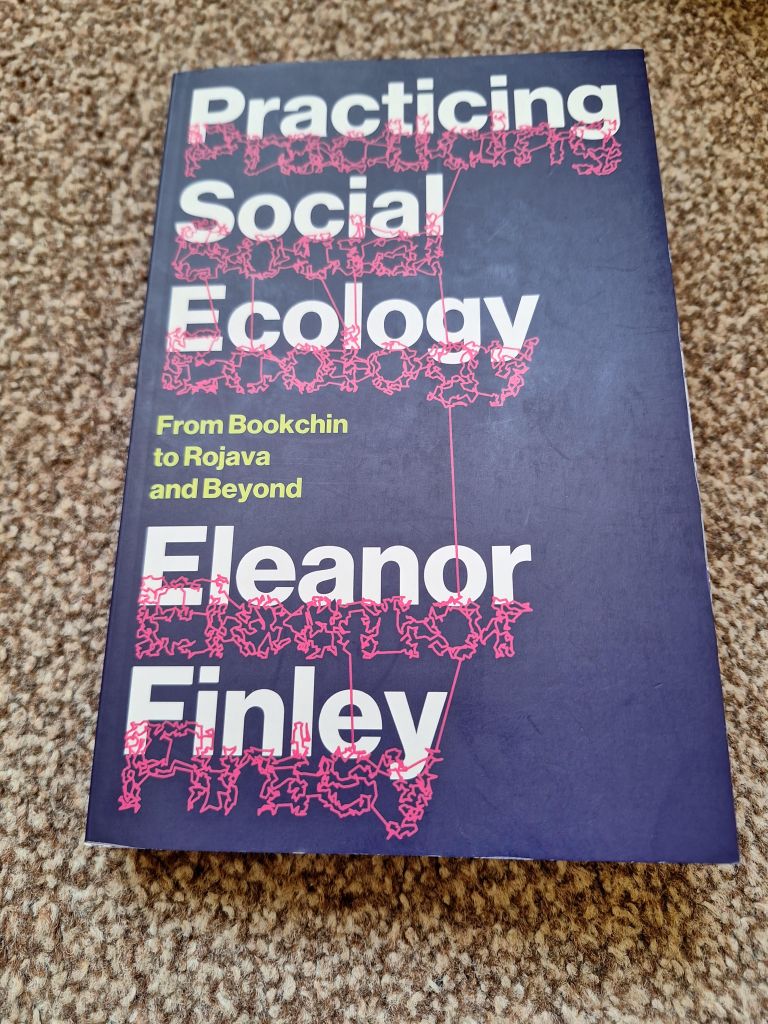

For the past eight years, “Google Murray Bookchin!” has been a slow-burning internet meme. When you google Murray Bookchin, you come across one of the most underrated philosophers of the 20th century, an eco-minded anarchist who eventually drifted onto his own path. But if you want a more detailed introduction to Bookchin, his ideas and his legacy than what Google can allow, you could try Practicing Social Ecology: From Bookchin to Rojava and Beyond, a new book by Eleanor Finley with a blurb from Bookchin’s daughter Debbie.

The meme portrays Bookchin as “a cunning grandfather”. This appeal of his stems from how he offers something that has long been missing from political academia: an inspiring vision. Some disciplines such as mainstream economics offer only minor improvements to the status quo. Others are mired in postmodernist cynicism. After the disappointments of previous visions — the failure of Marxism to create a better society and of anarchism to create any society at all — this is quite understandable.

But when we’re confronted with a dramatic polycrisis that leads to environmental breakdown, democratic backsliding, wars, economic inequality and more, visionary thinking is what we need. As Finley puts it, “Like the Gordian knot of ancient Greek myth, this multifaceted crisis will only persist until the right instrument strikes through its core.” I’ve written before about how I think Bookchin’s ideas deserve to be taken seriously. Especially as they have already been shown to work in an overlooked corner of the Middle East.

Finley writes a short, accessible book which is primarily aimed at those unfamiliar with these ideas, though those familiar may appreciate reading about Rojava and other case studies. It begins by discussing some key concepts that Bookchin developed, though others are introduced later. These include:

- Social ecology: the concept of studying human societies and nature as a single unit rather than our habit of treating them as separate systems. Some sources such as this book also use it as a broader term for Bookchin’s political philosophy, which he later also called communalism.

- Libertarian municipalism: the tactic of pursuing revolutionary change through people’s assemblies, direct democracy at the most local level. Bookchin advocated contesting elections so that candidates could give power to assemblies, rather than gaining it for themselves.

- Confederation: Higher levels of government, if they were to continue to exist, should be re-imagined as confederations of local assemblies.

There are others too. Although I’m more focused on his political ideas than his environmental ones, he had many interesting ideas about the latter. Certainly, his prediction that humanity was on collision course with nature was very prescient indeed. He also had a point in arguing that you can’t fully separate society and nature. Indeed, many societies don’t, especially indigenous tribes.

It should be noted that while Bookchin eventually stopped calling himself an anarchist in his final years, this was not an abrupt rejection of his earlier views. Rather, he drifted apart gradually, building a new philosophy on concepts like social ecology and libertarian municipalism that he had formulated within the anarchist tradition.

Revolution in Rojava

Female soldiers are the best-known symbol of Rojava’s revolutionary society

Finley then discusses how Kurdish movements built on Bookchin’s ideas, particularly through the writings of Abdullah Öcalan, the imprisoned leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) militant group. The PKK had originally been Marxist-Leninist, seeking to create an independent Kurdish nation-state. The fall of the Soviet Union had the effect of discrediting communism as well as cutting off a source of funding. Finley also suspects that they wanted a vision that was better suited to their rural and multi-ethnic lands.

Öcalan developed the concept of democratic confederalism, drawing heavily from Bookchin’s ideas and adapting them to local needs. Then when civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, the Kurds in Rojava, its northeast corner, had an opportunity to put the ideas into practice. They formed the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES), governed by elected councils and local people’s assemblies.

The experiment has faced enormous challenges, including invasions from ISIL and Turkey. Even after this book was written, Syria unexpectedly entered a new chapter with the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad. This is a mixed blessing for Rojava. Assad was no friend of the Kurds and relations with the new government have so far been good, but having had a stable détente with Assad, his fall opens up new uncertainty. Whatever its future, Rojava has achieved something truly remarkable, a role model for the Middle East for governing with popular consent, advancing women’s rights and overcoming religious and ethnic tensions.

Readers looking for the nitty-gritty on how this society functions may be disappointed. As she notes, when presenters come from Rojava to talk about their work:

Frequently, Western activists eager to understand Rojava’s system ask presenters how democratic confederalism “functions”. By “function”, they mean how often various communes meet, how many people attend assemblies, how citizens calculate votes, how delegates communicate, how communes produce and compensate their workers, and so forth. They are looking for numbers, metrics, and structures that can be reproduced. […] Although well meaning, many of these Western audience members have yet to grasp that what these revolutionaries are trying to convey is not a system that “functions” but a collective shift in consciousness.

The impression you get is that the local organisation of Rojava, including its assemblies and workers’ cooperatives, are often ad hoc and based on local needs and relationships, rather than bureaucratic rules. Exactly how things “function” in Rojava can be unclear and even messy, but as another visitor remarked, “Somehow, everything gets done.”

Other case studies

An Occupy Wall Street assembly

Finley also discusses her experience taking part in the Occupy Wall Street protests, another case study. One of the most interesting aspects of the Occupy movement was its use of ‘general assemblies’ to make decisions, with clever ideas such as hand signals and ‘human microphones’ to allow a wide range of people to have their say; the former has been used in many people’s assemblies since. Inspired by anarchism, these assemblies required consensus to make a decision, in some cases unanimous or at least a wide supermajority. She describes how it felt:

People naturally want a meaningful say in their own lives, yet nation-state politics deprive us of this. At Liberty Plaza, activists opened an agora, a space for public listening and hearing, for appearing and being seen. It allowed free equals to come together in mutual reflection about the human condition and the state of the world. People spoke passionately at general assemblies and spokes-council meetings because they deeply wanted to be heard.

My own limited experience with people’s assemblies also showed how much people could enjoy talking about things and listening to each other. Nevertheless, Finley reveals how their insistence on consensus was a major flaw:

Getting ten people to consent to the exact wording of a resolution is a long and delicate process. Getting 100 to do the same is impossible and, often, not even democratic. Young and/or wealthy individuals with relatively few obligations for work, childcare, or family responsibilities could outlast their peers in long meetings and have their resolutions passed without opposition. As the Occupy Movement’s popularity grew, meetings lasted for many hours, sometimes dragging into the night…

As Anthony McGann argues here, while requiring a supermajority for decision-making can benefit some minority groups, it is more likely to be the ones who benefit from the status quo — more likely advantaged minorities than disadvantaged ones. Majority rule, by contrast, is more favourable to the latter. The lesson: while it’s good practice for an assembly to aim for wide majorities and not just 51%, it is better to allow a majority as a fall-back option.

Other case studies Finley mentions include Barcelona en Comú and Cooperation Jackson in Mississippi State. Both of these are radical localist movements in which people’s assemblies played a pivotal role. If they weren’t inspired by Bookchin and Öcalan, they came to similar conclusions. They serve as inspiring examples of how you can re-imagine the possibilities of what local government and civil society can achieve.

Nevertheless, these movements had their limitations, which the book sometimes overlooks. I have noticed in my studies of localist parties and independents in the UK, they tend to fall apart by the time of their third election contest (examples: Kidderminster Health Concern, It’s Our County, Boston Bypass Independents, Ashfield Independents…). Though relatively successful, Barcelona en Comú and their Madrid counterparts have had some difficulties with both internal and external coalition-building, and never quite managed to repeat the impressive results of their 2015 debuts.

Pieces of the puzzle

Overall, Eleanor Finley has written a useful introduction to Murray Bookchin’s ideas and where they’ve led so far.

One last note: I often liken the task of renewing democracy to solving a jigsaw puzzle. Many of the thinkers and movements discussed above have found important pieces. None have found all of them. Neither have I. But let’s note a few more that others have found:

- Using citizens’ assemblies and smaller panels selected through sortition to advise elected politicians on their decisions. This results in better decision-making, especially as it avoids the infighting and selfishness that can often plague electoral politics.

- Making assemblies into colourful, social meetings that aren’t just about politics.

- Dividing assemblies into breakout groups. This makes them more sociable, helps shy and nervous people, and reduces the problem, as Peter Macfadyen puts it, that assemblies are often dominated by “loud men”. (I confess I can be one sometimes.)

- Challenging political parties with looser alliances of independent candidates.

Leave a reply to Independents in power — Flatpack Democracy 2.0 by Peter Macfadyen, review and analysis – Assembly Project Cancel reply