A recent poll from Ipsos sheds some light on the attitudes that underpin the rise of the far right. It found that across 31 countries surveyed, respondents by a 47%-27% margin were more likely to agree that their country needs “a strong leader willing to break the rules”. This included a 53%-22% margin here in Britain. The US was more divided, with 38%-25% in favour. This happens to have come out just as I was finishing a book called The Myth of the Strong Leader (2014, 2018 ed.).

The idea of a “strong leader” appeals not just to the extremes. It has long appealed to centrists too. An example is Tony Blair during his rivalry with John Major in the 1990s. In a 1995 parliamentary debate, he said, “I lead my party, he follows his.” In another in early 1997, Blair called Major “Weak! Weak! Weak!” Despite his collegial style, Major himself reacted to the first attack by pointing out disunity in Blair’s party.

But is a “strong leader” really a good thing? Part of the problem is that we confuse leadership with organisation. Leadership is about the role of those in charge, while organisation is about how the whole system functions. A disorganised government is one that can’t get things done, because it’s riven by factions that fight each other rather than working together. But a government can be organised without centralising too much power in the hands of one man, or more rarely one woman.

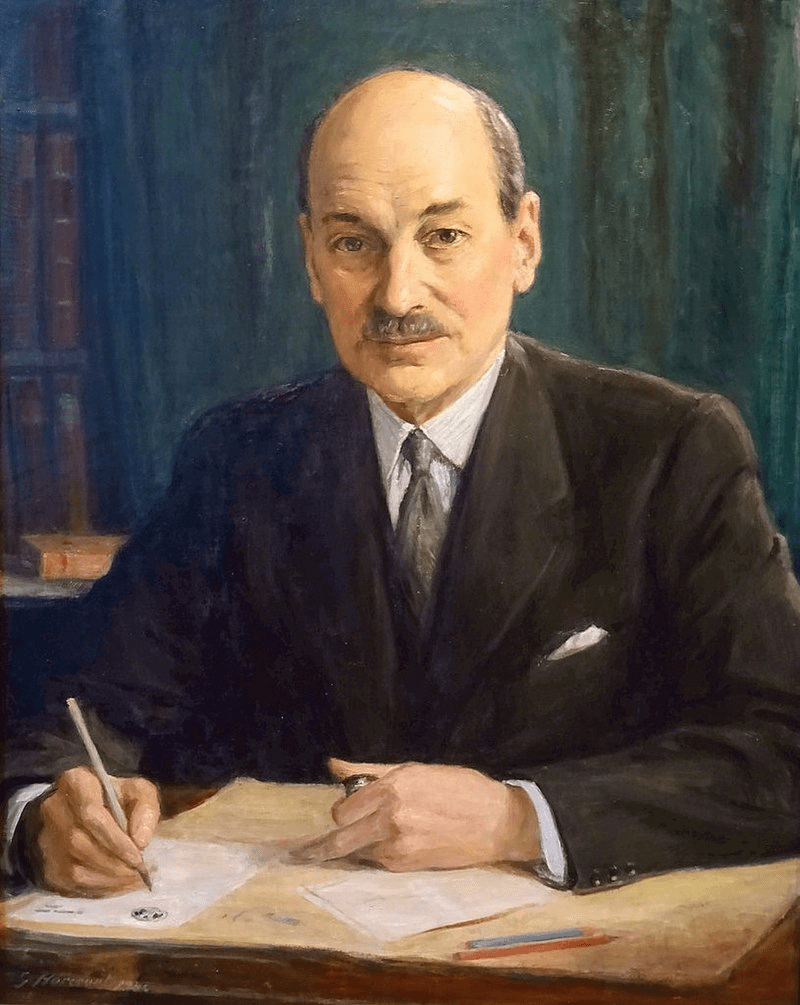

Clement Attlee did more than any other British prime minister to tackle poverty and social ills in little more than six years. Yet Attlee himself was a quiet, unassuming leader with a highly collegial leadership style. (Winston Churchill described him as “A modest man with much to be modest about.”) Many of his government’s key initiatives were delegated, such as Aneurin Bevin’s work to establish the National Health Service.

Leadership mathematics

The argument for making decisions by a wide group of people can be demonstrated with mathematics. Suppose people have to make a decision, and they make the right decision 60% of the time. If 11 people make the decision, a majority will be right 75.3% of the time, clearly an improvement on the 60% you would get from having just 1 making it. (This is calculated through the binomial distribution formula.)

With 21 people, this increases to 82.6%. With 31, it’s 87.2%. But it takes a bigger increase to get a similar rise, with 47 increasing it to 91.2%. This is a case of diminishing returns. As a result, while it is a case of ‘the more the merrier’, there is no point having too many people, especially as it may result in an unwieldly assembly.

Having more people involved in the decision-making brings other advantages. If the best decision requires a bit of creative thinking, someone is more likely to suggest it. But there are pitfalls too. Under some conditions, groups can radicalise to extremes that the individuals wouldn’t have gone too on their own.

Moreover, if the chance of making the right decision is below 50%, then the opposite is true, and it is better to make decisions with just one person, who will still get it wrong more often than not. This suggests that it may be a bad idea to decide your crime policy with a referendum, since most people don’t have the in-depth knowledge to make good decisions on the policy. A citizens’ assembly might be better.

This is obviously a simplified model. It doesn’t take into account numerous issues, such as how different people have different talents and the question of whether there really is a “right” decision. But I hope this illustrates the argument of governing more like Attlee, as long as you’re surrounded by people who are reasonably good at making judgments.

Now onto the book

A portrait of Clement Attlee, one of the leaders in the “redefining” category.

Attlee is one of the leaders who gets a positive appraisal in The Myth of the Strong Leader. The book was written by Archie Brown, an Oxford professor of politics best known for his work on Russia. It was written in 2014, almost a prescient warning. In a foreword from 2018, he weighs up his opinion on Donald Trump, who made a show of being “strong leader” while running a disorganised White House, thanks to a culture of infighting and Trump’s lack of vision and principles.

Most of Brown’s book is a series of essays on a variety of leaders, mostly from the Western world. Not surprisingly, British prime ministers have a lot of attention.

Brown discusses five types of leader:

- Redefining leadership: Democratic leaders who presided over a major policy shift. Examples: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Clement Attlee, Margaret Thatcher

- Transformative leadership: Leaders who presided over a peaceful change to a new type of government. Examples: Charles de Gaulle, Deng Xiaoping, Mikhail Gorbachev, Nelson Mandela

- Revolutionary leadership: Leaders who presided over a violent overthrow of the old government. Examples: Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro

- Totalitarian and authoritarian leadership: Leaders who presided over authoritarian governments, ranging from relatively benign to catastrophic. Examples: The three from the previous example though Atatürk is downplayed, Nikita Khrushchev, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini

- A fifth category is implied rather than named, but it could be described as non-redefining democrats who brought only minor policy shifts. Examples: Harold Macmillan, Ronald Reagan, Tony Blair

I’d have liked a book like this to also discuss findings in sociology and psychology the subject. It can be dry at times, although it’s peppered with some nice anecdotes. One of the underrated transformational figures is Adolfo Suárez, the prime minister of Spain who presided over the transition from Francisco Franco’s regime to democracy. He even persuaded Franco’s rubberstamp parliament to vote to abolish itself.

Adolfo Suárez, one of the leaders in the “transformational” category

The importance of collegial leadership

Overall, Brown’s message is clear and justified: democratic leaders tend to fare better when they work with others instead of concentrating power around themselves. There can be exceptions, as implied with his positive appraisal of Charles de Gaulle despite his centralising instincts. But Brown notes that De Gaulle was an unusual case among democrats anyway. Authoritarian regimes likewise fare better if they have a collective leadership rather than a one man show.

Though this book is solely about government leaders, rather than business and NGO leaders, it’s a conclusion worth listening to for anyone wanting to lead anything.

Leave a reply to Learning from the Jeremy Corbyn movement – Assembly Project Cancel reply