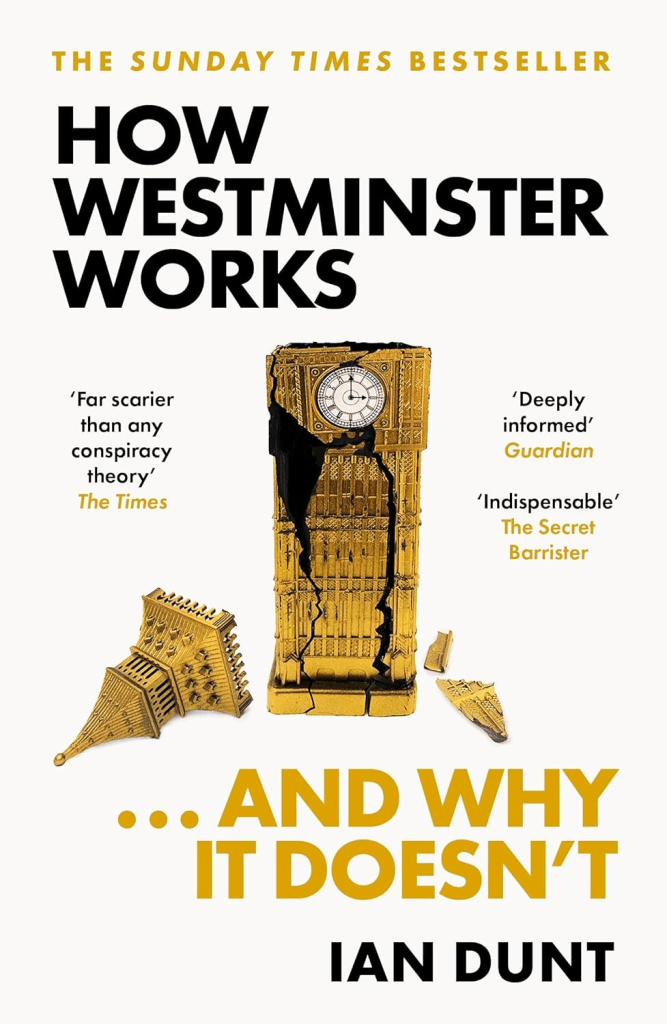

The British Parliament is sometimes called the “Mother of Parliaments” but perhaps a better analogy is an elderly granny. That’s certainly the impression you get from Ian Dunt’s 2023 book How Westminster Works… and Why It Doesn’t, with the emphasis decidedly on the latter.

This book is essential reading for anyone wanting to get close to British politics. Dunt offers clear analysis of the organs of the government, as well as a chapter on the press. He has clearly done his homework, listing over 80 people he’s spoken to at the end. It includes some well-known politicians like Nick Clegg, Neil Kinnock, Rory Stewart and Peter Bone. There are also some important behind-the-scenes figures like Gus O’Donnell, the most senior civil servant from 2005 to 2011.

I was aware of many of the problems being discussed, but Dunt argues that it’s even worse than it looks. He is perhaps overstating it to make his point. He mentions how the House of Commons has been short of women while overrepresenting Oxbridge graduates, but not how these have reduced in recent years. Overall, I found his unflattering portrayal of institutions mired in stodgy tradition and perverse incentives to be all too believable. Like the King of France in the dying days of the Ancien Régime, the prime minister and government are both too strong and too weak.

Too strong

On the one hand, there is a dangerous and absurd lack of checks on their power, all the more worrying as the UK and wider world are increasingly vulnerable to the far right. The first-past-the-post voting system tends to give one party a majority that is way out of proportion with their actual support (taken to a new extreme last year when Labour won 63.2% of the seats with 33.7% of the vote). As this majority is rigidly whipped to support the government, the government can nearly always pass any bill it pleases, which can’t then be struck down by the courts.

Meanwhile, the theatrics of the Commons do little to scrutinise bills, and it doesn’t help because:

MPs are given no instruction in how to scrutinise or even read legislation, let alone introduce it. Most remain largely ignorant of parliamentary procedure throughout their time in Parliament, no matter how long they’re there. And this is not a failure by the political parties. It is a choice.

Moreover, an increasing number of laws are passed as statutory instruments (i.e. ministers’ decrees), bypassing Parliament altogether. One of the most disturbing parts of the book reveals how two laws from the 2019-2024 Parliament gave the home secretary effective powers to decide by decree the rules for when protestors could have liberties taken away by court order. The orders could:

impose ‘anything’ in the form of restrictions or prohibition, including barring the protestor from particular places, or meeting particular people, or participating in particular activities. It even allowed the authorities control over their social media accounts.

Too weak

Yet despite having too much power, governments also struggle to do things that people would actually want them to do. Dunt mentions how many problems from the tax system to government structure have gone unaddressed and devotes a chapter to the government’s shocking inaction over the 2021 fall of Afghanistan; one he doesn’t mention is the deadlock on social care. The problem is that they have the power but not the organisation.

Part of the problem is that ministers and senior civil servants move offices so often. They are not experts in their departments’ subject matter and have little time to learn about it before they’re again moved on. The sheer centralisation of power makes it worse. Ministers have to make so many decisions, like whether to approve grants to a school or hospital that in other countries would be done at a local level. David Lammy discusses the decisions he had to make outside of working hours during an earlier time as a minister:

You can be making 30, 40, maybe 50 decisions a day. […] There’s something almost about the human capacity to absorb the material. There’s something that really feels like this isn’t humanly possible.

Though Dunt agrees with many of the criticisms over ministers’ special advisors (“spads”) and their increasing use over time, he argues that they sometimes can be useful for overworked ministers. This may explain the lack of appetite to remove them.

If there’s one thing that Dunt misses, it’s how the governance arrangements of the UK are, as a Commons committee put it in 2022, “some of the most centralised among democratic countries in the world”. Spending projects are infamously concentrated in London and the South East; the Institute for Government notes that this region received 41% of English R&D spending when it’s home to 32% of the population. While Dunt blames this trend on the Treasury’s economic philosophy, having so many decisions made in Whitehall doesn’t help either. It’s also why people keep writing to their MP for help with cases such as benefits when these would be better off being dealt with by others such as local councillors.

Just right?

Indeed, the only parts that come off well are the select committees, and, incredibly, the House of Lords. I agree with him. If you’ve ever seen the Lords, the quality of debate is so much better than the Commons, because they have what the latter needs but lacks. The Lords are less tribal and careerist, bring a wider range of skills and aren’t controlled by a single party. It’s the place where bills get the best scrutiny. That said, he agrees that the appointments process is flawed and it’s difficult to ignore how anachronistic it looks. I wonder what he’d think of Assemble’s proposal to replace the Lords with a citizens’ assembly.

Dunt’s proposals for reform are sensible, including giving the Commons a proportional voting system and control of its business. Many of them sound little but could have a big impact, such as moving the prime minister out of Downing Street and using less jargon in the Commons. It’s a sensible laundry list. There’s a hint of assembly democracy, when he suggests that citizens’ juries could scrutinise proposed bills. But as he notes, most governments have only made modest patches, usually during their first few years in office. It’s a similar case with decentralisation.

That’s why we need something more than just sensible ideas. We need to make more decisions by assembly democracy — including a citizens’ assembly at a national level.

Leave a reply to Parallel thinking — Failed State by Sam Freedman, review and analysis – Assembly Project Cancel reply