Western England is often associated with rural life and retirement, but it also has a number of quirky towns with a bohemian, independent atmosphere, such as Glastonbury, Totnes and Stroud. And then there’s Frome (read: “froom”), an attractive medium-sized town in Somerset. During a brief stopover there last year, I was struck by how friendly people were in the shops and cafés.

Frome has produced quite a few pioneering social initiatives since the early 2010s. Among them are a ‘library of things’ for borrowing equipment such as drills, a community fridge, a neighbourhood plan and a charity to help the disadvantaged, many now copied in other towns. When the district council closed the public toilets due to cutbacks, Frome set up a scheme where local businesses would let passers-by use their toilets. Also notable is a scheme from the local health centre to combat loneliness, by connecting as many people as it could to local community groups, as reported in The New York Times. Perhaps that’s worth another post in the future.

But also part of Frome’s newfound reputation for independent-ness is the town council. In 2011, a group of residents formed a political party called Independents for Frome, actually a coalition of independent candidates. They won a majority of the seats, beating the traditional parties, less than four months after they had formed. If you’d asked me back then to predict what would happen next, I would’ve predicted they would be a wishy-washy do-nothing movement that would fall apart by Christmas.

Instead, outside reports paint a similar picture of how they not only held together but became unusually active and inventive for a parish (i.e. village) council, making the best use of their limited powers. They were behind many of the initiatives mentioned above and had a supporting role in others like the loneliness scheme. By raising the local tax and supporting housebuilding, they also showed that they could make courageous decisions. In the three elections since, they went on to sweep every single seat on the council.

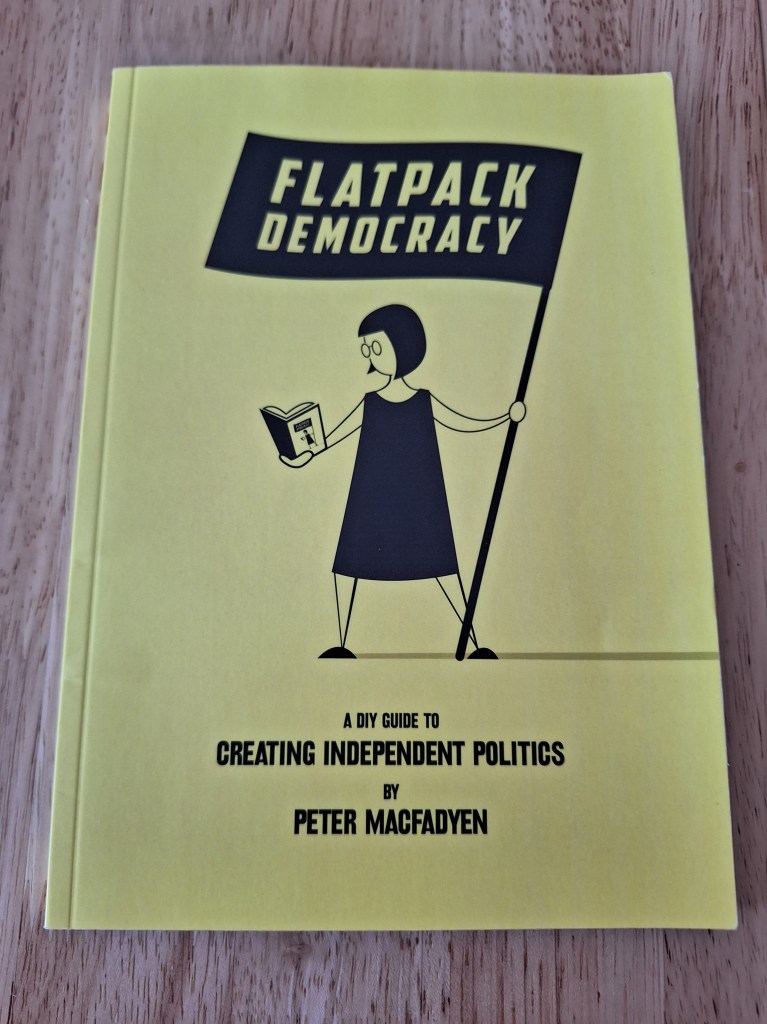

The book Flatpack Democracy is a first-hand account of the revolution by Peter Macfadyen, a councillor for their first two terms, and also a handbook for anyone wishing to try something similar. The title refers to his idea that we have the components to build a better system, it’s just a matter of doing the work to assemble it.

Though the book is in need of editing (“Barak Obama”) and a proper conclusion, it is more importantly a valuable revelation. Given that some organisers of people’s assemblies hope to stand independent candidates, it offers vital lessons for what you can achieve and how to get there. It is useful for warning of pitfalls that can trip up a fresh-faced political movement. For example, a large proportion of the vote in local elections is postal and cast a few weeks before election day, so don’t wait until the last week to get your campaign going.

One remarkable moment is when the council discussed some projects they could spend money on in return for more tax money and asked which ones they wanted. The people they spoke to wanted all of them. This is emblematic of an ancient trend in politics, that voters can accept paying more taxes if they have more control over how their money is spent

St John’s Church, a local landmark

The Party that is not a Party

So why did Independents for Frome succeed?

Independents for Frome agreed to disagree: Most parties are founded based on an ideology or a policy, and they typically vote as a monolithic unit. The whip system means that those who fail to vote for the party line, determined by its leadership, can get kicked out. In practice, the decisions on how they vote owe more to party tribalism than principle or the public interest. The public has become all too aware of this, and this is likely a reason for the growing cynicism towards politics.

Independents for Frome had none of this baggage. They brought many different political perspectives to the table. As this study shows, a mix of perspectives tends to lead to better decision-making. Macfadyen emphasises the “Ways of Working”, a code of conduct that their candidates agreed to. It contained points such as:

Avoidance of identifying ourselves so personally with a particular position that this in itself excludes constructive debate.

Yet you still get the impression that while they were independents, they were united, in a way. They were united by a sense of belonging and purpose, as well as an aim to work together. That allowed them to stand with something more than what independents usually offer, which tends to be a message of “Vote for me, I’m local and a nice guy”.

Independents for Frome listened: Too often, “consultation” is used dishonestly, by councils and governments that have already made up their mind and are merely box-ticking a legal requirement. This is the “DAD” approach — Decide, Announce, Defend.

Macfadyen emphasises how the council talked to the locals to find out what people wanted from them. Some of this was done through a mini citizens’ assembly. Much of it was done through public meetings. To make the public more comfortable and included in these discussions, the council used outside facilitators and ditched many stuffy formalities in their language and procedure.

Besides the obvious, this also addresses the problem of how to govern without parties. On its own, it would leave a council or government without a clear direction, but it can compensate by listening more to the public.

Independents for Frome used neutral outsiders: These played two formal roles. one was that the group hired outside facilitators to conduct public meetings. If you have someone from within preside over the meeting, there is a danger that their own sympathies will influence who they call up to speak. Or, even if they don’t, the attendees may suspect they are.

Another was the crucial selection process for candidates. From their founding meetings, really a form of people’s assembly, they recruited a selection committee whose members would not be standing for election. By leaving it to an ad hoc committee of outsiders, rather than a club of insiders, it took away the factionalism. This may be why they avoided the common problem with independent alliances — their habit of falling apart after about five years, as seen in Kidderminster, Boston and Herefordshire.

Frome wasn’t too large: This is something overlooked in the book, that Frome had one town councillor per 1,700 residents. By contrast, the average member of parliament represents over 100,000. A US representative represents over 750,000.

In a small electorate, it is easier to for candidates to get elected and then govern based on local messaging and connections. In larger electorates, politicians are inevitably more dependent on campaigning machines and national messaging, which is why independents are far rarer at this level.

In their book 101 Ways to Win an Election, Mark Pack and Edward Maxfield suggest that you need 1 campaign volunteer for every 200 voters in the electorate. This should give you an idea about whether an independent candidate stands a chance.

Parties, especially left-wing ones, were weak in Frome: In 2011, the outgoing Frome Town Council was controlled by the Liberal Democrats*, who were losing support nationally after forming a coalition government with the Conservatives. The latter, the second largest party on the outgoing council, fared better that year but still lost votes. Labour, the party that made the most gains that year, had never been strong in Frome. That year, the town was uniquely fertile ground for a centrist or left-wing alternative.

(*A semi-outsider party whose position has varied between the centre left and centre.)

Their second contest was held on the same day as the 2015 general election. The Conservatives were in a stronger position, topping the poll in the local parliamentary seat by over 30 percentage points and probably also in Frome itself. There was a risk that Independents for Frome would be drowned out by the general election campaign. Yet neither of these stopped them from romping home. The general election may have even helped, because unlike the national parties, Independents for Frome could devote all their efforts to the local contest.

By contrast, when other groups tried to create a similar independent alliance in Winchester and Bath, they not only faced the problem of larger electorates, but they also had to fight the Liberal Democrats when they were making gains nationally. The lesson? Independents tend to be weakest against left-wing parties that are gaining support nationally and running a spirited ground campaign. But that may not be true when they compete against right-wing parties.

Beyond Frome

In this later interview, Macfadyen offered a similar view to me for the current decline of democracy:

Even at this community level, people get elected as representatives, and then the public sit back, expecting them to do stuff, and get angry when they don’t. For me that method of representative democracy doesn’t really work anymore, if it ever did, because people are more empowered, more knowledgeable, have access to more facts. So it makes much more sense to have a relationship in which the councillors are facilitating conversations, are catalysing actions, but then are bringing people in.

Is flatpack democracy the answer? Are there limits to what it can accomplish? Independents for Frome have inspired similar movements in other parts of the country, including Portishead, Uttlesford, Hexham and several towns in Devon. They have even inspired some abroad. But it has usually been treated as an interesting case study rather than an example to copy widely; nothing similar has been attempted in most of the nearby towns. Perhaps this lack of drive reflects the apathy towards England’s powerless local governments and more broadly representative democracy in general.

Even if it can gain more traction, there are questions as to whether the ‘flatpack’ approach could work at higher levels. Could it manage the challenge of winning larger electorates while still being a genuine grassroots movement? Can the approach form a national government, where the stakes of governing are higher?

Despite my disillusionment with political parties, I am not sure if we can get rid of them altogether, especially at a national level. Perhaps they are still needed to get things done. Perhaps they are still needed to give clear choices. But there is a burning need for them to step away from the aspects of party politics that voters despise. More movements like Independents for Frome could put pressure on them to do that. So could more assembly democracy.

Leave a comment