The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony is an excellent guide to humans’ powerful group instincts, written by psychologists Jay Van Bavel and Dominic J. Packer. Our group instincts drive us to work together in groups and have underpinned all of our greatest achievements, from the building of Stonehenge to the man on the moon, and all of our worst, from wars between tribes to wars between nations. The book kicks off with a milder negative example, an account of how a German town came to be divided by shoes.

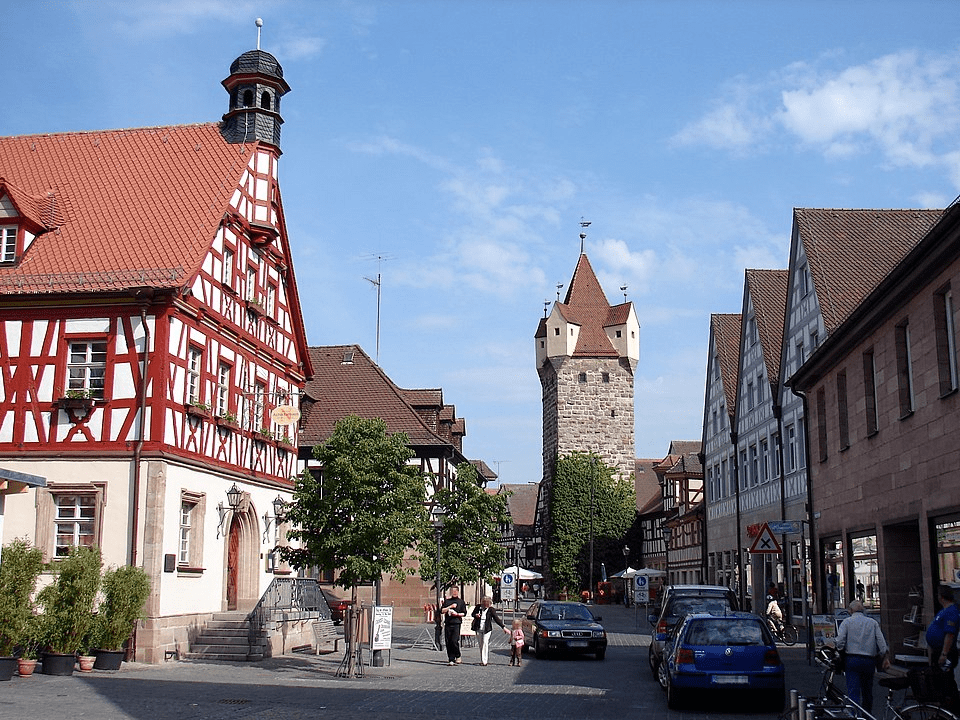

You probably haven’t heard of Herzogenaurach, an “idyllic” smallish town on the outskirts of Nuremberg. But you may have heard of two companies based there — Adidas and Puma. Both are world-famous makers of shoes and sportwear. The companies were founded by the brothers Adi and Rudi Dassler, who had jointly run a factory in the town. For unclear reasons, the two brothers fell out and started rival companies on opposite sides of the river. No prizes for guessing which one founded Adidas.

Because so many locals worked at their two factories and wore their shoes as a visible sign of it, it created a social division in the town. The authors describe its effects:

Walking about town, people would look down at each other’s shoes, making sure they interacted only with members of their own group. Thus did Herzogenaurach become known as the “Town of Bent Necks” …[E]ach side of the town had its own bakeries, restaurants and stores. Townsfolk from the other side were refused service if they wandered into the wrong establishments. Families were divided. Once-friendly neighbors became enemies. Dating or marrying across company lines was also discouraged!

After the deaths of the Dassler brothers in the 1970s and economic changes, the Great Shoe Divide gradually waned. By the time employees of the two companies played a friendly football game in 2009, there was a sense it was over.

What’s surprising about the Town of Bent Necks is how the cause of division was so unimportant. You could understand people getting divided over politics and religion. Questions like what economic policies work best or how to get to an afterlife both sound like things that ought to raise strong opinions. (Though there’s a catch with the latter, as we’ll see.) But sometimes social division can happen for no real reason at all.

The Power of Us is an excellent overview of what social psychology has taught us about our group instinct, aimed at a general audience. It is an accessible read with compelling accounts of case studies and experiments. The book was first published in 2021 and while it’s not their main goal, the authors write with an eye on the ongoing (and since worsened) crisis of democracy, though also an eye on creating something more timeless. The book does not hold all the answers to our problems, but there are some valuable lessons.

(Below: Herzogenaurach)

It’s about the coalitions

One of the most important ideas in the book is the idea that human identity is coalitional. We can belong to many groups. This reminds me of how the politician Charles Kennedy once said he was “a Highlander, a Scot, a citizen of the UK and a citizen of the European Union at one and the same time.” But we also identify with many smaller groups: our families, our social circles, our clubs, our workplace, our demographic groups and many more. This reflects how our ancestors lived in bands, but not bands with rigidly fixed membership. Bands also had allies on the outside and sub-units within. This could be something as simple as a few members going off to forage or collect firewood.

This has important consequences as we face perplexing dilemmas on how to heal a politically polarised society like the United Kingdom and especially the United States, where partisan or ideological identities overshadow shared ones like citizenship. Differing opinions can turn into different facts, partly because honest disputes about facts are inevitable but more worryingly when they aren’t. It can feel like reality itself is falling apart, because as the authors point out, “All reality is social reality”. This is dangerous territory.

Some good news, not mentioned by the authors but by Steven Pinker in Rationality, is that hateful beliefs like the Pizzagate conspiracy theory often aren’t as bad as they look. Their adherents don’t really believe them, at least not as facts. Rather, these are mythological beliefs. Like religion, these are things that someone may believe to be true but that they keep at a distance and do not act on. Supporters of Pizzagate who believed that Hilary Clinton was involved in child sex trafficking, were in fact capable of being civil and even friendly with her voters. But how were the latter supposed to know? Nor is the separation absolute, as seen with the gunman who did take it seriously.

The authors bring some good news of their own. It is surprisingly easy to get people to refocus their identities onto those they share. They mentioned this intriguing experiment with English football fans. Fans of Manchester United did a task that reminded them of their love for the team, then they walked to a building to complete a study. On the way, they past an actor who had pretended to be injured. How many of them would help him? It depended on what sort of shirt he wore:

- Manchester United shirt: 92%

- Liverpool (a rival club) shirt: 30%

- Plain shirt: 33%

In this particular experiment, it didn’t really matter if someone came from a rival outgroup or no specific outgroup. Rather, they felt far greater concern for those from the ingroup, a specific moral circle of people they cared for. But if they were instead reminded of their identity as football fans rather than fans of one team, the results were different. They became just as willing to help Liverpool fans — but not the guy in a plain shirt!

This reinforces my support for Murray Bookchin’s idea that we need to refocus politics on people’s shared identities as citizens and residents of their local towns.

Lessons in overcoming bias

(One of the George Floyd protests in London, June 2020.)

The decade before this books’ publication had been a mixed one for social justice causes in the Western world. The social media age has certainly turned many of them into divisive causes that were preoccupied with winning symbolic victories and playing into the hands of the far right. These problems can overshadow the genuine gains, with growing public awareness of problems like police brutality and accidental bias. Social progress quietly marched on, even as societies loudly struggled to cope with it.

The authors devote a chapter to “Overcoming Bias”. Although not as directly relevant to assembly democracy as other parts of my review, my view is that any project like what I’m doing needs to make an “Equality Impact Assessment” as it plans and goes — it is a legacy of those aforementioned gains that I would write that. How can a new movement make sure it doesn’t cause unintended discrimination? The authors note how biases hidden in good people can create discrimination in many differ ways, but also how they can be overcome with small fixes.

It raises a question too about how to overcome social divisions. It is inevitable and understandable that people with ethnic minority or LGBT identities will want to bond with those who share and understand their unique experiences, and to campaign for change. But this kind of self-sorting comes with the risk of creating division and worsening discrimination, especially when the identity comes with visible signals and symbols, such as a headscarf, a turban or a rainbow flag on a social media profile. A few markers of identity are impossible to hide, such as gender, skin colour and accents.

As the authors had noted in the previous chapter:

We have noticed a tendency both on social media and offline for people to diminish and even make fun of identity signalling. Sometimes disparaged as “virtue signaling” or “showing off,” the implication is that displays of identity are self-promoting or disingenuous. And certainly they can be. But signaling identities is also a vital part of the way that people navigate the social world. It is how people establish standing and how fellow members of valued groups find one another.

There is no reason why this problem should be permanent. Such divisions can pass. There was a time when being a Protestant or Catholic in the wrong country could get you killed. Today, these churches are at peace. It does help that you often can’t see someone’s religion just by looking at them (or their shoes). But some Christians wear a cross necklace, and few would bat an eyelid at that.

The authors don’t fully address how to solve the contradiction, which to be fair is not something they had to do. But the best I can recommend is deep canvassing, by knocking on doors to have heart-to-heart conversations. It is one of the few methods known to reduce prejudice.

Dissenters are the cure

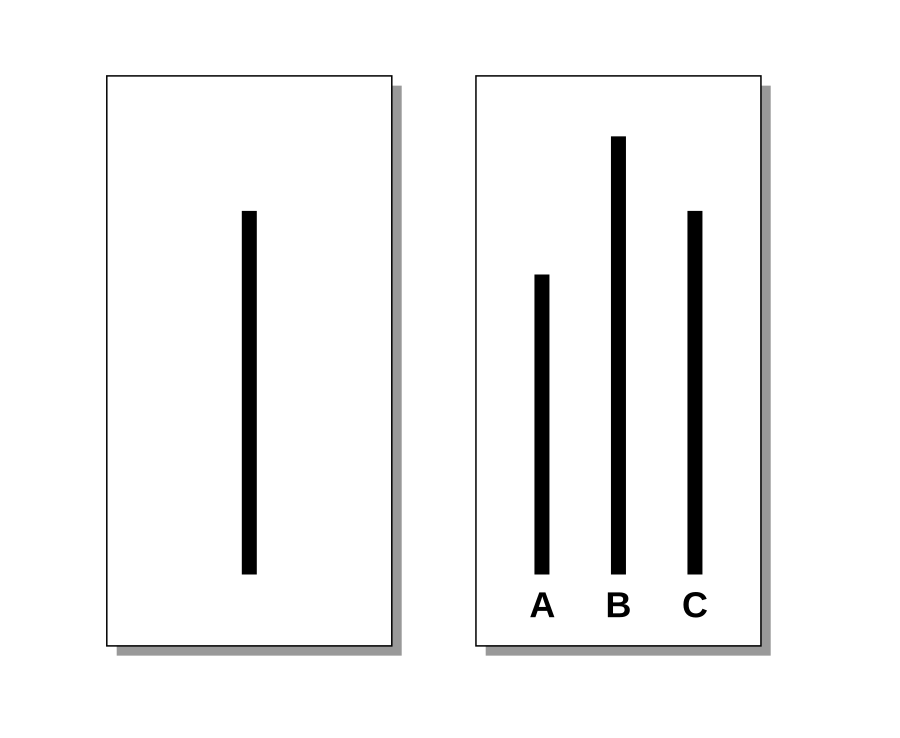

(Cards from Asch’s experiment on conformity.)

One thing I like about this book is that the authors aren’t just rehashing the standard psychology textbook, but discuss where familiar stories of the field has been questioned or challenged, sometimes drawing from their own work. You may have heard of the Asch and Milgram experiments, as I had, but the authors also note how those experiments have been sensationalised at times.

Yes, they show how humans can be led into absurd or even horrifying acts of conformity. Solomon Asch famously showed that people could be led to say the wrong answers for questions about the lengths of lines, in a task that they got right 99% of the time in isolation. More shockingly (pardon the pun), Stanley Milgram showed that ordinary people could be coerced into inflicting lethal electric shocks on an innocent man. But there were nuances and limits to this. Asch’s subjects often gave out the right answers in spite of the peer pressure. Milgram’s subjects did sometimes balk, if they felt sympathy for the victim.

Conformity isn’t always bad. In fact, we likely evolved our conformity instincts because it helped. I can imagine that even if a band of our ancestors made a decision that not all its members agreed with, it was better for them to go along with it, rather than rip apart the band. Today it can help us work together and keep fringe attitudes in check. But how can we keep its dark side at bay? This is especially relevant when talking about the discussions at a people’s assembly.

As both experiments found, dissenters are the cure. A single dissenter who is willing to say “The Emperor has no clothes!” can break the spell of conformity. The authors discus this in the context of organisations and groups making decisions, as well as in how public bystanders react to a crime or a medical emergency when others are reluctant to intervene.

This is a challenge, because when someone disagrees with the decisions of a company or government, it is tempting for others to assume they are being disloyal to it. The authors use the example of how the company Enron radicalised itself into an epic fraud and came undone, but worse has happened when the same pattern of radicalisation played out in governments, above all Nazi Germany. If dissenters had felt comfortable speaking out and been listened to, the pattern could’ve been prevented.

But as the authors note, not all dissent is good. One type of dissent that genuinely harms an organisation is strategic dissent, over the actual goals of the organisation rather than how to achieve them.

This is why, if you’re criticising an organisations’ decision, it helps to argue against it on the grounds that they won’t help its goals and values. Rather than falling into the trap of raging against dearly-felt identities, you can look for their goals that you agree with and argue that they do not work in favour of those goals. This is what Yascha Mounk did in The Identity Trap. (He too notes the power of dissenters.)

Conclusion

The Power of Us offers a fun, accessible read that gives an excellent overview on group instinct to those who’ve never studied this area of psychology. Readers well-versed in the matter will be less surprised and perhaps itching for more lessons that are directly applicable to their work. There are many points that could be discussed in this book, from a convincing defence of their field from problems with replication and allegations of left-wing bias, to ruminations on leadership and the famous case study of a doomsday cult that thought the world would end on 21 December 1954. It didn’t, but the cult still held together.

While not all it directly relates to people’s assemblies, it does provide important messages. Because an assembly forms a group in itself, people can develop new identities based on belonging to the assembly itself. The book strengthens my already confident that people’s assemblies can overcome divisions of identity, as many have done in cities like Hull. Whether they can change society as a whole is less clear.

Leave a comment