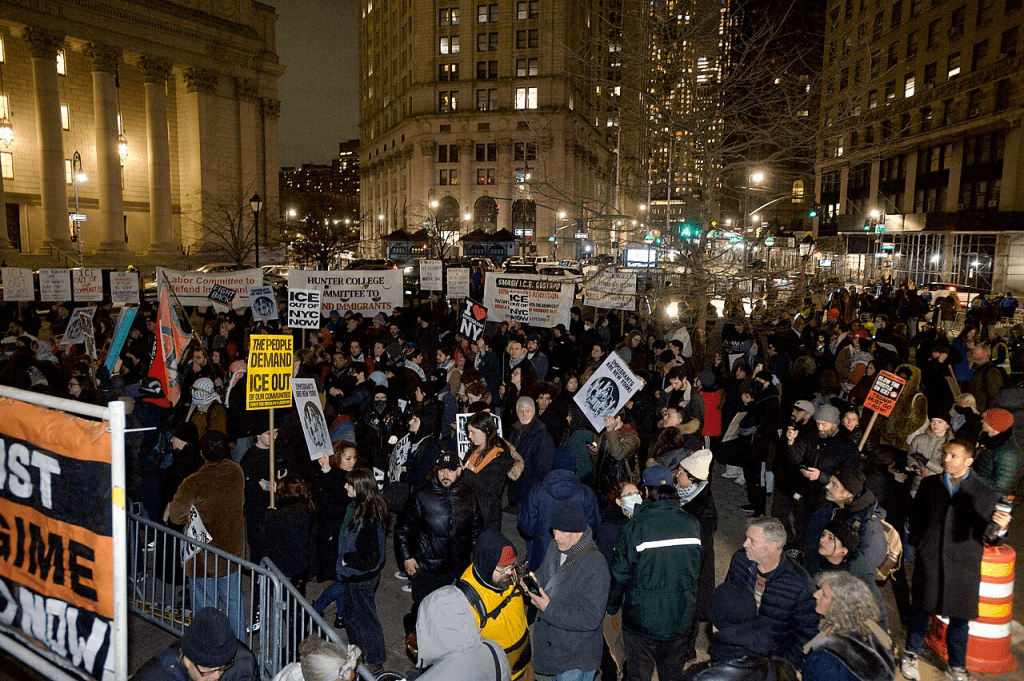

A protest against the killing of Renee Good last Wednesday, only hours after it happened.

The 2010s saw more people take part in political protests than any decade before. The 2020s are shaping up to be bigger still — on the day I write this, the US is facing another big wave of protests over the killing of Renee Good. Yet very few of those protest movements achieved their goals. Some even backfired.

The Arab Spring toppled dictators and shook the complacency of others, but only Tunisia made any progress towards democracy, which has since been reversed. The George Floyd protests were the biggest and widest waves of protest in the Western world and they did win concessions, but most of these were ceremonial or even performative. I myself marched against the raising of tuition fees in late 2010, but still ended up having to pay them.

A few years ago, people started asking why this was, particularly when Vincent Bevins published his book If We Burn, one of my earliest reviews. Central to his book is his experience in Brazil, where he watched a progressive protest for free public transport escalated into a general protest against politics, undermining a centre-left government that had until then been popular. The most memorable bit is when the movement’s five-point agenda was set by a guy in his bedroom posing as a hacker from Anonymous.

Part of the problem is that protests never have been all that effective anyway.

Understand their limits

May 1968 protests in France

Firstly, what is the point of a protest? Is it to tell the government that people don’t like something? Obviously that’s part of it. But a government can find out through things like opinion polls and social media. We usually sense that protests are serving a purpose of putting pressure on the government. But can they really be pressured by people standing in a town square?

As Steven Pinker noted in his new book, which I’m currently reading, protests “generate common knowledge”. In the story The Emperor’s New Clothes, the townspeople all know the emperor is naked. All the boy does is tell them something they already know. But he also teaches them something new; the townspeople realise that everyone else knows. The emperor’s nudity becomes common knowledge. Protests become useful when they act as an emperor-has-no-clothes moment for the government. To everyone, they say: “Some people oppose this”; to those who agree, they say: “You are not alone.” Those two become facts.

My tuition fees protest may have been good for making the opposition to the rising tuition fees a well-known fact, but that was not enough. Public opinion was more split on them. The median voter might’ve grumbled a bit about cuts like these, but they were still sympathetic to the ruling party and their belief in TINA (“There is no alternative.”). So the Conservatives were not only able to press ahead with their austerity agenda but remain in power for another 14 years.

This isn’t really a change from the 1960s, when there was a burst of protest movements but few of them brought noteworthy change. Perhaps the biggest at the time was the movement that almost brought down the French government in May 1968. It did win concessions, such as an agreement to raise wages and a snap election — only for the centre-right to win it by a landslide.

The first lesson here is: don’t just rely on protests, even though they have their place. There’s two sides to this. One is to recognise that protesting may not go far enough. The answer is not violence. As Erica Chenoweth notes in her influential research, violent movements are less likely to succeed than non-violent ones. Instead, when protesting fails, the next resort should be non-violent but disruptive direct action.

Seek wider support

A 2019 protest in Hong Kong.

But as we’ve seen with Extinction Rebellion, even disruption has its limits, if you don’t have wider backing in society. Yet this problem is all too common, partly because protests tend to attract the people with the most left-wing views.

And as Bevins notes in his book, a recurring problem is that protest movements have ended up radicalising. For example, during the 2019 Hong Kong protests, it started as a campaign for autonomy within China, in line with what most locals wanted. But it became overshadowed by a small anti-Chinese minority. This was compounded by another problem; the risk of being hijacked from outside. In this case, outside attention focused on Hong Kong as a geopolitical background between two great powers, rather than people who wanted to a say.

Bevins blames the problem on “horizontalism”, the fact these movements have no leader or organisation. But as I put it in my review, “For all his criticism of horizontal movements, it seems that the real problem then is a lack of good vertical ones.” Loose, decentralised protest movements need to be complemented with tight, well-organised campaign groups. I like the analogy of an ecology here.

A successful movement won’t please everyone, but it needs to be anchored in the wider realm of public opinion. So protestors that hit an impasse should organise campaigns to expand their support. Once the protest’s over, go out and talk to people. Organise local people’s assemblies or places for discussion.

Furthermore, protest movements should demand citizens’ assemblies, one of Extinction Rebellion’s genuine successes. A randomly-selected citizens’ jury can have great legitimacy with the public, while also making much better decision-making than elections and referenda.

Protest assemblies?

An Occupy assembly in Washington Square Park, New York, in 2011.

Finally, there’s the question on what to do during the protests themselves. Inspired by the Occupy Movement, I suggest that protests themselves should have assemblies. Though they lacked small groups discussions and made the mistake of rigidly insisting on consensus, Occupy assemblies proved an asset to the movement. Unlike the other movements Bevins describes, it remained true to its goals despite a lack of leadership. There was no radicalisation that we might associate with the word “mob”.

The other factor is that it turns the protest into a warm, social experience, which is a lot more fun than standing around in a crowd for hours. Imagine too how it would look to people watching on the TV or internet, seeing protests sat round in small discussion groups.

This can have other benefits to making it sociable. It can be fun to take part in a protest — I’m one of many who’s felt something of a ‘protest high’ from it. But one thing that deters people from getting involved in them is that it’s often a boring prospect. Protesting often involves standing around for hours, holding placards and chanting. You’re with people to some degree but often not socialising.

Ever since the rise of mass media and especially television, protests have had their uses. But the lesson of the past 15 years has been clear: we need more than protests, and better protests too.

Leave a comment