As the philosopher Roman Krznaric put it in a recent opinion piece on how to save democracy, “The rise of citizens’ assemblies is the most significant innovation in Western democracy since women won the right to vote a century ago.” So it is worth learning from this previous innovation as to how assembly democracy can catch on. What did the suffragettes and suffragists get right and wrong?

I did an A-Level History module on the women’s suffrage movement in the UK. Historians sort its activists into two types. The suffragists used traditional campaign methods, such as holding meetings, staging petitions and marches and lobbying politicians. Their main organisation was the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), led by Millicent Fawcett (the statue pictured above). Most members were women but there were also some men.

By 1903, some of them found the NUWSS too cautious. They broke off to form the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), led by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. The all-female group (a few men joined in their campaigns) were first called suffragettes as an insult, which they started using with pride. Initially they differed by doing noisy but non-violent stunts such as unfurling ‘VOTES FOR WOMEN’ banners at public meetings. But when those brought diminishing returns, the group resorted to methods that were more radical and violent. (There was a similar liberal-militant split in the American women’s suffrage movement, only militants were far less prominent.)

It started first with vandalism, such as breaking windows. When suffragettes were arrested, they went on hunger strike, and for that were subjected to brutal force-feeding. Then it escalated into a campaign of arson and bombings, some of which had clear intent to harm people. In total, 4 people were killed and 24 were injured by the campaign, respectively including 1 and 2 suffragettes.

What the suffragettes got wrong

It may seem surprising that the suffragettes are often commemorated as role models. Is it morally justified to use violence if you’re denied the vote? Perhaps sometimes. But there is a good reason why the suffragettes are not imitated today. Arson and bombings are a terrible tactic to win a cause like this, both then and now. The militant campaign undermined the cause of women’s suffrage, though there were other obstacles too, including opposition from most Conservatives and some Liberals like Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916.

Whether or not the militancy changed minds is less clear, but it certainly embarrassed supporters of women’s suffrage while galvanising their opponents. Some of latter, like the Viscount Helmsley in a 1912 Commons debate, put it in bluntly misogynist terms:

The way in which certain types of women, easily recognised, have acted in the last year or two, especially in the last few weeks, lends a great deal of colour to the argument that the mental equilibrium of the female sex is not as stable as the mental equilibrium of the male sex…

Every MP who spoke against women’s suffrage in that debate cited suffragette violence as a reason. Supporters of women’s suffrage also perceived damage, such as David Lloyd George in a 1909 letter:

The action of the militants is ruinous. The feeling amongst sympathisers of the cause in the House is one of panic. I am frankly not very hopeful of success if these tactics are persisted in.

Modern historians on the matter tend to agree. In the end, it was partly the suffragists’ non-violent campaigns that won the day.

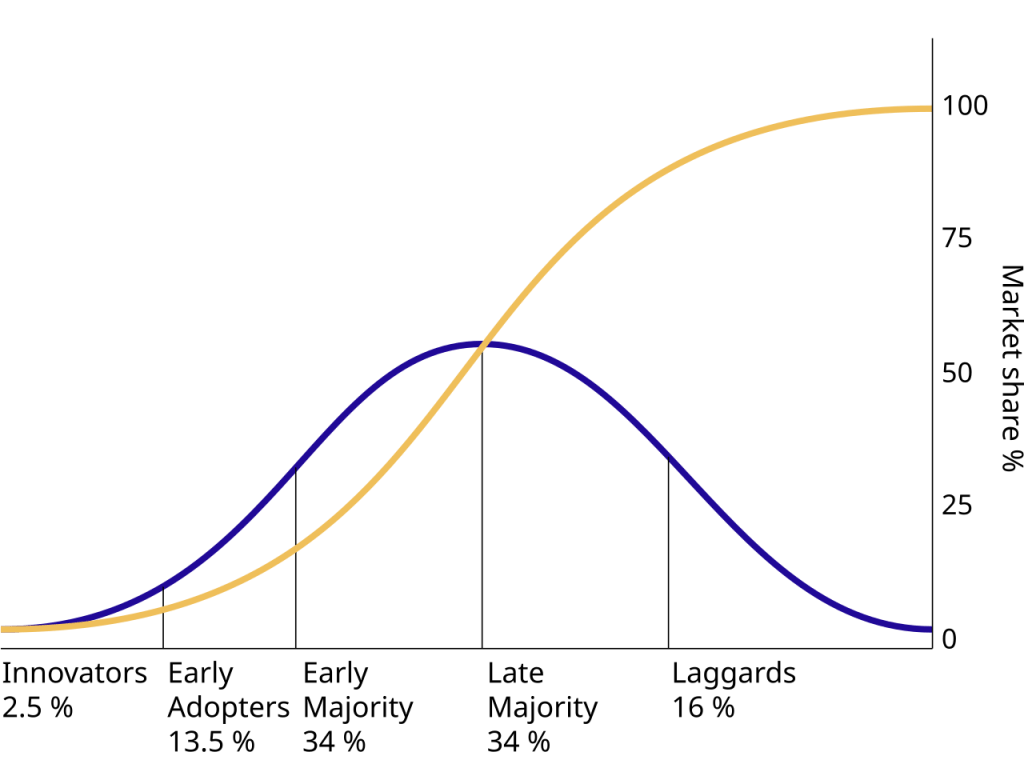

But there were others too. Like many social changes from the spread of Christianity among the Romans to the growth in support for same-sex marriage, women’s suffrage can likely be modelled as a diffusion of social innovation. This is a model where it is assumed the innovation can spread among the people independently of any campaign, through everyday conversations and interactions, until it reaches the ceiling, much like the orange S-curve on the chart above. Although we cannot be sure, as there were no opinion polls in the early 1910s, it appears most of the public supported women’s suffrage by that time.

Women’s suffrage, in other words, was what I term a winning formula. Both women and men who heard about the arguments for women’s suffrage tended to switch in favour to supported it. Women had an obvious incentive to support it, but men were won over by sympathetic arguments too.

What the suffragettes got right

In modern times, the suffragists are mostly forgotten, apart from Millicent Fawcett who is commemorated by the name of a feminist society and more recently the statue above in Parliament Square. Even then, many passers-by assume it’s a statue of a suffragette. The British public tends to speak as though it was the suffragettes won women the right to vote, using the term loosely instead of drawing a distinction with the suffragists. David Bowie never wrote a song called Suffragist City. All of this partly reflects what the suffragettes got right.

Before it escalated out of control, their early non-violent campaigns may have helped. At a time when the media was growing and transitioning from being mostly local to mostly national, the suffragettes saw how a publicity stunt could get their cause noticed and talked about, in a way that cautious suffragist tactics could not. Millicent Fawcett acknowledged this in 1906, before the WSPU turned militant:

They have done more during the last 12 months to bring it within the region of practical politics than we have been able to accomplish in the same number of years.

The suffragettes also understood the importance of creating a good visual image. Though less important in the days before television and the internet, images could still be circulated widely in a newspaper. Humans respond far more to visual images than text and speech. It wasn’t an accident that the suffragettes generated pictures like the front page above. The suffragettes deliberately wore fashionable women’s clothing during their protest actions.

This is the same reason why Ed Davey has used stunts like riding down waterslides and falling off paddleboards to advertise his party’s policies. It’s not just about generating headlines, but also visual images.

What no-one saw coming

There’s another lesson too. Some studies on the consequence of women’s suffrage (such as here and here) find that it tended to result in more economic growth and more spending on social projects. Why is that? In most countries, there are only modest differences between how men and women vote. Rather, like earlier democratising innovations, women’s suffrage made politics more responsive to the people. In turn, people were more willing to entrust the government with more of their taxes.

While that may sound very left-wing, it’s also worth noting that in the century before women’s suffrage, the Liberals formed most of Britain’s governments, whereas in the century after, it was the Conservatives. Egalitarian values fared better than the parties that championed them.

Lessons for assembly democracy

What does this all mean for assembly democracy? Whatever one may think of Assemble’s publicity stunt in the House of Lords, itself inspired by the suffragettes, I don’t think anyone’s planning to promote assembly democracy through a campaign of bombing and arson.

We live in a different time to the suffragists and suffragettes, but many of the methods of changing society are broadly the same. What also hasn’t changed is that it comes with no shortcuts. We might live in an age where things can go viral on the internet, but you cannot force something to go viral. Nor it does this favour the truth and just causes; falsehoods spread more easily. Occasionally it can encourage protests in favour of a fairer society, as with the murder of George Floyd 2020, but even those had clear limitations.

Headline-grabbing publicity stunts can help, especially if they produce a good visual image. By the 1970s, they could travel better on a TV screen and in colour. Today, they can travel better on social media. But in every age, they bring diminishing returns when repeated and are not shortcuts to the hard work of bringing social change. The publicity only has meaning if it is built on a foundation of grassroots support, whether it’s spread through organised or disorganised means.

Ultimately though, the best way to bring change at the top, such as a new law, is to have a winning formula that can spread at a grassroots level. The behind-the-scenes campaigns of the suffragists are mostly forgotten, but they were often doing the best that campaigners for women’s suffrage could do. The best way to encourage the spread of assembly democracy is to start it in your own area.

Leave a comment